‘The demand is greater, the parallelism more strenuous’

What are civil society and business demanding towards the G7 Summit? Questions to Julia Harnal from Business7 and Mathias Mogge from Civil7. An interview by journalist Jan Rübel.

The G7 Summit is once again supposed to be about thinking big. But the question remains: how is that possible in light of the multitude of crises? Can we even get out of crisis management?

Mathias Mogge: The G7 countries must think big – that is their duty. The last Elmau summit was in 2015, when the Paris Climate Agreement was adopted and the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 were agreed. Today, seven years later, I find the results disillusioning. We have not really made any progress. Let’s look at Germany: every year we fail to meet our climate targets, unless there is a pandemic. The G7 countries have an important role model function – due to their economic power, they undoubtedly also have the means to set a good example.

Julia Harnal: And the G7 countries need common core values. When it comes to starvation and climate, everything is pointing in the wrong direction – even before the pandemic, which is clearly exacerbating the negative trend. When I look at the economies, however, I see that a lot has gone well for the companies since 2015. Of course, we don’t have a clean record. But the voluntary sustainability goals that all companies set for themselves—and verify—are better than anything that existed before Elmau 2015.

Mr Mogge, how much better do you think the voluntary commitments have been since 2015?

Mogge: It’s a start, but it’s not enough. Some companies are abiding by them, but we have also seen in the past that governments definitely need to set targets.

The G7 should be less hesitant.

When we think of the Due Diligence Act, we demand more regulation of due diligence from civil society, because otherwise the environmental and social goals would not be met. Regulatory measures are absolutely necessary.

Do you agree with this sense of urgency, Ms Harnal?

Harnal: A lot can be accomplished with regulatory policies, but it must not be over-regulated. For example, we would like to see a more hands-on approach and stronger initiative on sustainable supply chains at G7 level by politicians. This is already moving in your direction, Mr Mogge. Several companies decide to rethink their operations when they see how many others are already participating. The platform is now established: through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Benchmarking Alliance, there is a recognised method that examines the sustainability of supply chains. Politicians outline the framework, multilateral platforms set the process, and companies must follow suit. It is also clear that we all stand behind the European Commission’s Green Deal. Short-term crisis management has nothing to do with going back to the past now and throwing everything away that we had already committed to politically and regulatorily.

You can’t achieve all your goals when you put a few of them on hold. The demands have become greater and the parallelism more strenuous! Nonetheless, we want to commit to tackling the climate and hunger goals together and in parallel.

Mogge: The crises are also mutually amplifying. Ecological issues cannot be put on the back burner. There is nothing more important now. We must look at the problems as a whole. Picking and choosing will not get us anywhere.

Mr Mogge, a communiqué by the C7 states: the urgency of changing the system has never been greater. What does that mean?

Mogge: It means that small changes and more money is not enough. We need a different way of doing business and a different response to the massive inequalities we have seen for decades. There are incredible crisis profiteers. The rich are getting richer, and the poor are getting poorer. There really needs to be a systemic change. Therefore, the rich countries need to ask themselves: what is the impact of our policy? How do we influence the global trading system? For example, agricultural subsidies alone are a definite step in the wrong direction. Something is being promoted that in the end creates more harm than good – there is no contribution to an ecological transformation.

Ms Harnal, what do companies think when someone calls for a systematic change?

Harnal: Change means jumping from one path to another – this would not do justice to our complex world. However, when it comes to a substantial, long-term, but also profound transformation of the systems, we are all in. And we want these discussions, because that’s the only way to give these intentions momentum.

Are there perhaps solutions that address both, the short-term crisis, for example the food shortage due to the Ukraine war, and long-term demands?

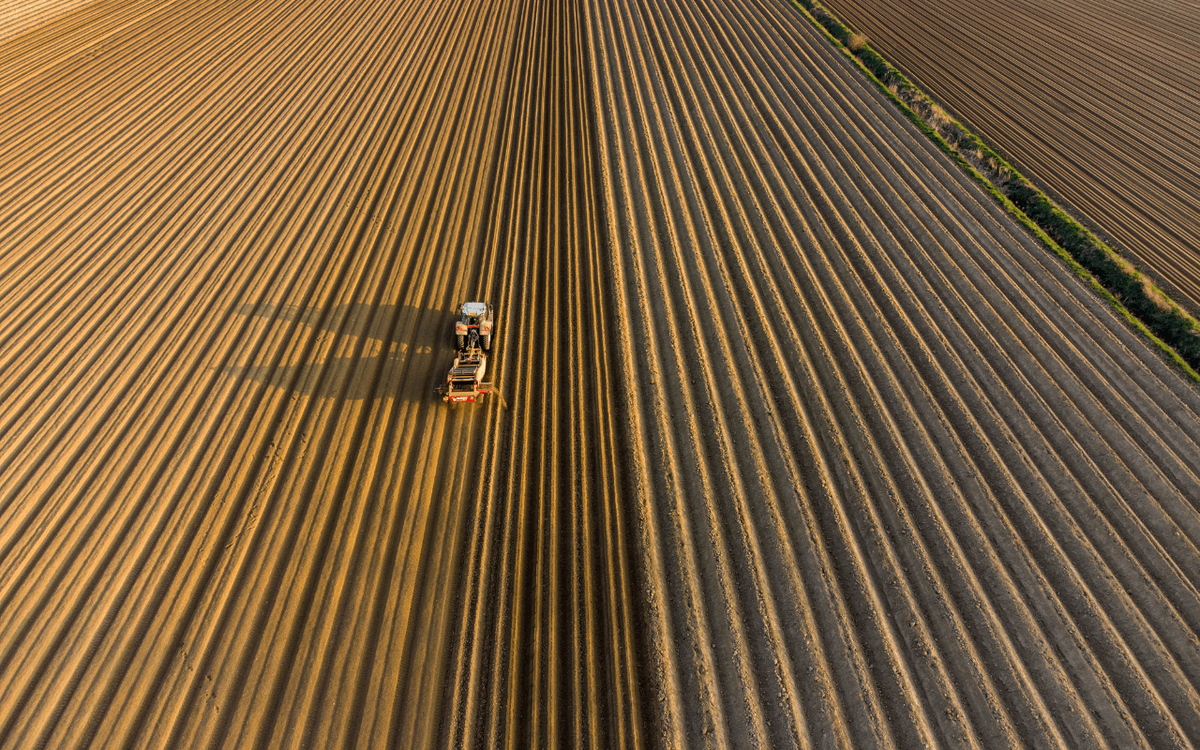

Harnal: The technology solutions for more precise farming are a great example. If the farmer reduces fertiliser usage, he can earn more money. The technology is ready to do that – and simultaneously addresses climate, hunger and social justice. As far as subsidies are concerned, we would like to see every public funding tool scrutinised for its actual outcome. So far, this has not been thought through consistently.

A few people now think it’s time to cut corners and focus less on environmental protection. Are they right? For example, should more fertilisers now be used worldwide to reduce the losses caused by the Ukraine war through higher grain harvests?

Harnal: We do not want to cause short-term hyper-activism and pay the price for negative environmental effects to offset a theoretical increase in production. The problems with climate, technologies and access to them are much more significant and require long-term consistent action. Besides, the fertiliser, for example, is not there right now, so this is nothing more than a theoretical debate. Real game changers are topics involving healthy diets, meat intensities, meat consumption and food waste and loss.

Mogge: Production can and must be increased in the Global South, especially in countries that are heavily dependent on imports. I am not against agricultural trade either. But when it comes to investments, they should go where they can lead to big yield increases and improvements – and where it is about better, more diverse nutrition. This long-term thinking must not be lost in any debate about acute hunger relief in the shadow of the war.

It also applies to the recently launched Global Alliance for Food Security: this initiative is good and important, but we must be careful that it does not degenerate into a fad – and in three years we are in utter disbelief that hunger has risen again.

Do you see the risk of frantic efforts that accomplish nothing?

Mogge: Yes. The pressure is incredibly high now to feed the acutely hungry people. That is correct and necessary. But we also need staying power. We need an additional 14 billion euros annually from the G7 countries to at least lift those 500 million people out of hunger – as was promised in Elmau in 2015. The 430 million euros pledged by the German government for the new Alliance are a positive sign. But it will not suffice. We need to make the funding more permanent.

Harnal: The initiative should unite all stakeholders who can do it. Those who implement pragmatic solutions and provide products. Mr Mogge, I completely agree with you: helping people help themselves is the way to go. This must happen quickly. Money is good. It is a catalyst. But now it is a matter of action. We expect dynamic leadership from the BMZ so that all those who can make a difference can make their contribution.

What can the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations do right now?

Mogge: Hmm. Well, the Rome-Based Agencies (RBAs), including FAO, are extremely important organisations in the context of global nutrition. Ideally, they should work closely together and offer appropriate advice. The United Nations has the capacity to look at global nutrition: how much is produced? How much is consumed? How much is in storage? No one can do that better than the UN. The key players are there. But it requires collaboration among the organisations in close alliance with science, non-Government Organizations and the industry.

Am I summing this up correctly: The RBAs are not doing enough?

Harnal: If the strong countries don’t do their part, you can’t blame the RBAs either. At the G7, everyone is called upon to do their part. Of course, we are not satisfied with the sluggishness, the complexity and the lack of clarity either. You need the will to change this.

Mogge: FAO is a membership organisation. These types of structures are not easy to change. Governments are having a hard time with overdue reforms, like the UN Security Council.

What is the political responsibility of companies, Ms Harnal – in the argumentative dichotomy of crises, market and sustainability?

Harnal: We have taken a clear position on European values, but I wouldn’t call it political responsibility. Our mission is more of a human, social and economic nature. We want to design technologies that make a positive contribution to the transformation. And of course, we have the financial means to do so. Based on our business experience, we were able to document and implement precise projects, infrastructures and initiatives in the Global South. Here, companies can consistently provide funds for investment and innovation.

Mr Mogge, do you see companies as having political responsibility? Are you concerned with more than investment and innovation?

Mogge: Absolutely. What Ms Harnal says sounds good. But the organisations that work in the Global South keep noticing that large, transnational companies sometimes cause poverty, for example, by investing in a way that deprives smallholders of their land. They get their hands on land through corruption. Through their investments, some companies contribute to a country not building its own sustainable economy. That is still a fact in many countries.

Harnal: I just wanted to make sure that the political leaders are still held accountable to do their job. For us, it is the ethical and moral framework in which we resolutely operate. Our mission is that we respect all international agreements on human rights, fair supply chains and safe technologies, and we make sure that this happens on the ground.

Is there a core demand for government leaders that you, as representatives of civil society and business, are making jointly or for your respective division?

Harnal: We demand a pragmatic implementation of the political will...

...to ensure food security in the short term. In the medium to long term, food systems must be transformed. This requires close coordination between the ministries so that we can finally break the deadlock.

Do you feel the same way, Mr Mogge?

Mogge: Considering the shrinking space for civil society engagement, we call on the G7 to set up a task force. Also, much more needs to be done in the area of conflict prevention. And the debt crisis is an issue where we all expect a strong sign from the G7. Debt relief is needed now. The G7 also needs to be clearer about how it intends to achieve the 1.5-degree target on climate change. And finally, there is a need for regulation in the healthcare sector: the coronavirus pandemic, for example, has shown that a temporary suspension of certain patents is needed for medicines and vaccines. This is the only way to facilitate access for large parts of the population.

Is that sufficiently diplomatic, Ms Harnal?

Harnal: I can’t say anything about the pharmaceutical industry. Regarding the 1.5-degree target, I would like to add that we are finally positioning the issues of food and agriculture in the climate conference process in such a way that it leads to results in Egypt in November. Everyone will be there to discuss what needs to be done; unfortunately, little usually happens with a view to concrete action. This is where the G7 process can do crucial groundwork.

In other words, building bridges between the G7 and the COP?

Mogge: The frequently discussed ‘Food Day’ should now take place at COP27, a whole day dedicated to the focus on food and climate. It is only to be hoped that the G7 governments will recognize this and commit to it.