Foreword

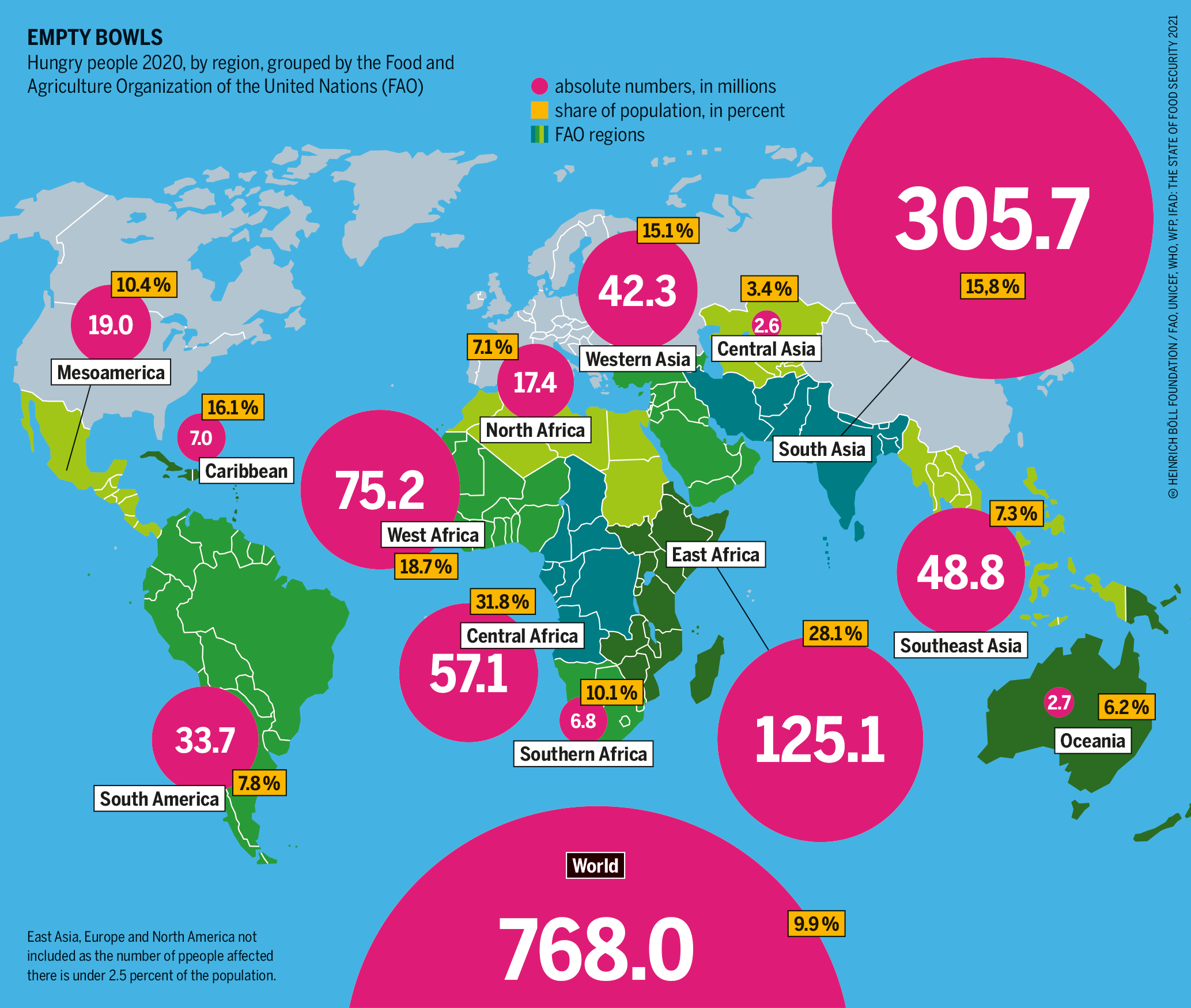

In 2020, 768 million people suffered from hunger and undernourishment. That is almost 10 percent of the global population. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations expects these numbers to rise further as a result of the economic crisis triggered by covid-19, extreme weather events, and conflicts.

At the same time, many millions of other people are unable to enjoy a healthy diet. In the developed world, demand is rising for food from food banks. Unbalanced diets, nutritional deficiencies and obesity have emerged as major burdens on health services.

Hunger and malnutrition are not accidental by-products of our food systems. They are the consequence of lacking regulation and existing power imbalances. They are a moral disaster and a political and social call to action.

With this publication we want to make a contribution to a lively social debate. We want to present the causes of hunger and malnutrition and show that clear political rules and strategies are needed to counter these developments. We want to show that hunger and malnutrition are the consequences of injustice, instability and poverty – and that policies must therefore also address these underlying causes.

The inspiration for this publication is the United Nations Food System Summit 2021. For the first time in the history of the United Nations, a summit will be devoted exclusively to our food systems. The Summit could become a catalyst for real change, as participants will discuss food system transformation.

But the signs are that the summit will not adequately address the social and political causes of hunger and malnutrition. It might turn out to be a missed opportunity.

It is possible to create sustainable, just and healthy food systems. For this to happen, it is key to strengthen political structures that truly focus on the right to food, on healthy nutrition, and on protecting biodiversity and the climate.

Barbara Unmüßig, Heinrich Böll Foundation

Alexander Müller, TMG Research

CRISES

A FUTURE WITHOUT HUNGER

Since 2017, the number of hungry people around the world has been rising again. Poverty, war and natural disasters threaten food security especially in Africa and south Asia.

KRIEGE

CONFLICTS FEED HUNGER, HUNGER FEEDS CONFLICT

Warring parties drive people off their land, kill livestock and damage crops. They destroy infrastructure and transport networks, disrupt markets and push food prices up. Conflicts are one of the main causes of hunger. But a lack of access to food can also be a cause of war.

MALNUTRITION

GOING HUNGRY, AND TOO MUCH OF THE WRONG THINGS

Malnutrition is increasing worldwide. Too little food inhibits early childhood development, while too many empty calories from sugar and fat may cause cardiovascular diseases or diabetes.

POWER

FOOD BUSINESS, BIG BUSINESS

From land ownership to seed supply to food retailing: food value chains are marked by their concentration in a few hands. The imbalance of power between large companies, smallholders and consumers results in malnutrition.

FOOD POVERTY

YOU MIGHT NOT CHOOSE THE FOOD YOU EAT

In a wealthy country like Germany, can everyone get enough healthy food? It’s not that simple. Income, education and employment are closely linked to health.

Crises

A future without hunger

Since 2017, the number of hungry people around the world has been rising again. Poverty, war and natural disasters threaten food security especially in Africa and south Asia.

In 2015, the world community set itself the goal of ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030. But figures from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) tell a different story. Since 2017, hunger and undernourishment have been increasing. In 2020, 768 million people had too little to eat – almost 10 percent of the world’s population. A major reason for this is poverty. Some 1.8 billion people worldwide live in poverty and have to make do with less than 3.20 US dollars a day. Nearly 700 million are subject to extreme poverty, living on less than 1.90 US dollars a day.

The corona pandemic has exacerbated this situation. The World Bank estimates that almost 100 million more people have fallen into poverty as a result of COVID-19, a rise of 12 percent between 2019 and 2020. The pandemic has caused a global economic downturn. Lockdowns, job losses, declining investment and falling exports, along with the collapse of the tourism sector, have led to severe losses of income in many countries and have worsened poverty.

While the population of developed countries have long had to spend a declining proportion of their income on food, poor households in the Global South still have to devote most of their income to food. Rising food prices are therefore an acute threat to food security. FAO’s food price index has risen continuously. In comparison to 2020, it is about 30 percent higher in 2021.

The majority of poor people live in rural areas and make their living from agriculture. In many countries in the Global South, far more than 50 percent of the people work in agriculture, which provides them with both food and work. That is why employment-intensive, smallholder farms will continue to be central in the fight against poverty. But the situation of the urban poor is also an increasing concern. While less than 40 percent of humanity lived in cities in 1980, by 2020 the figure was over 56 percent. That means that cities must also be part of a comprehensive strategy in the fight against hunger, and that urban agriculture, for example, should be promoted. Local initiatives in urban agriculture generate employment in production, processing and marketing, and are especially useful in improving income opportunities for women.

In 2021 FAO emphasized that hunger is essentially caused by poverty and inequality. Fighting hunger means fighting inequality too. The land rights of vulnerable groups must be recognized and secured. This protects against chronic poverty and enables investments in sustainable land use. Long-term investment in climate-adaptation measures also become profitable for smallholders if their land tenure is secure. It is especially important that women have secure access to land. Combating inequality is also necessary within the family: equality generally has a positive impact on the food security of the household and the well-being of children.

People who live in poverty are less resilient than those who are better off. They are less able to react to acute economic or ecological crises. This is serious because the frequency and intensity of ecological crises has greatly increased. Since 1960 the number of natural disasters worldwide has risen tenfold. For millions of people around the world, climate change brings more frequent and more serious flooding, drought and storms, which account for 90 percent of all climate-related disasters each year.

Around a billion people live in countries, mainly in the Global South, where the official structures are not in a position to cope with the ecological crises that are to be expected by 2050. To deal with the challenges of climate change, systemic approaches such as agroecology are needed that take a holistic view of agriculture and food production. To prepare for the impact of the climate crisis, it is not enough to focus only on individual elements of agricultural production, such as the development of drought-tolerant crop varieties.

Economic and ecological crises are often made worse by violent conflict. In many countries, such crises occur in combination. The world community can therefore successfully fight hunger and malnutrition only if it raises the ability of vulnerable groups to respond to crises and ensures their access to food. A focus just on agricultural productivity will not be sufficient. Policies against hunger can be successful only if they strengthen resilience.

War

Conflicts feed hunger, hunger feeds conflict

Warring parties drive people off their land, kill livestock and damage crops. They destroy infrastructure and transport networks, disrupt markets and push food prices up. Conflicts are one of the main causes of hunger. But a lack of access to food can also be a cause of war.

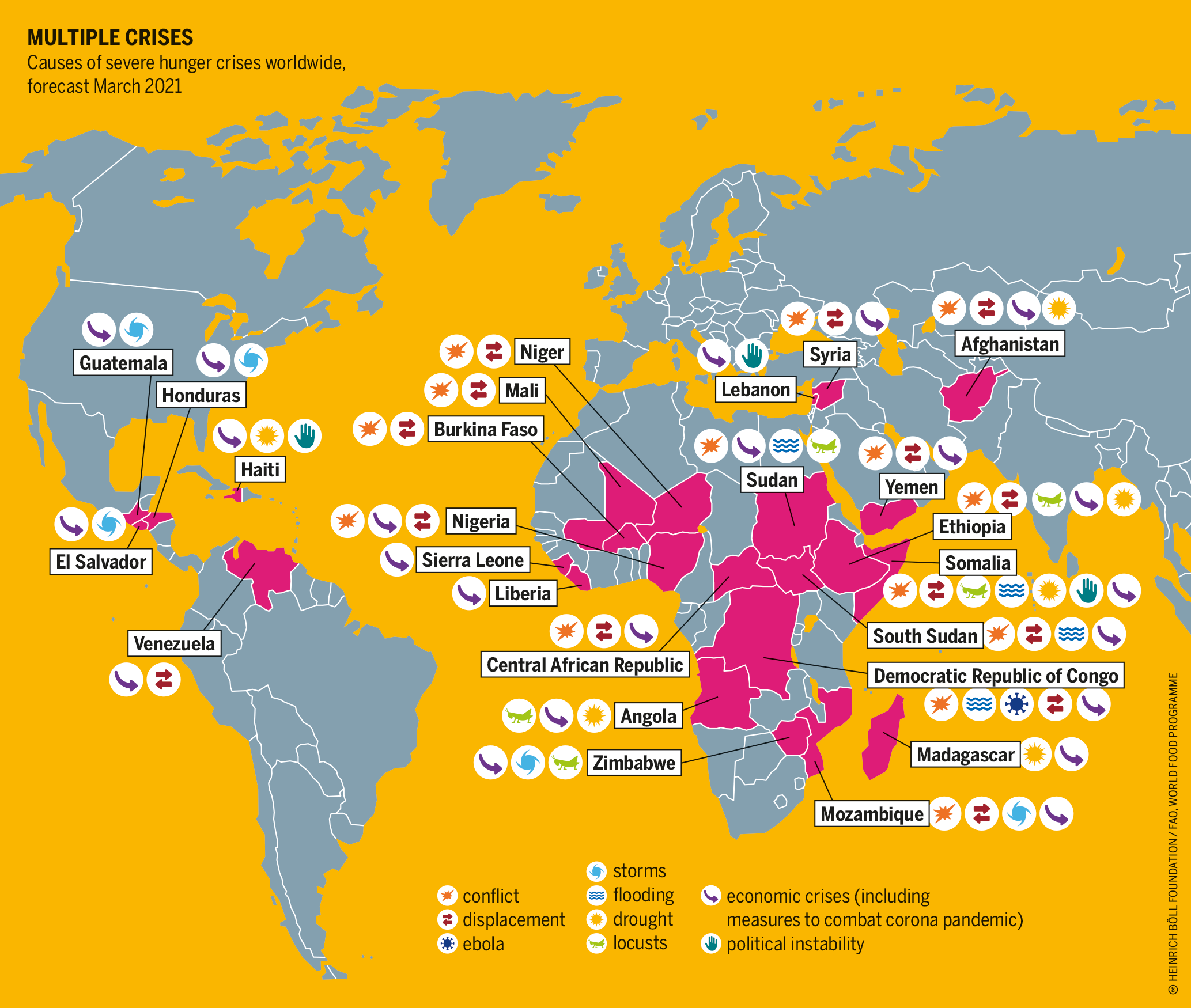

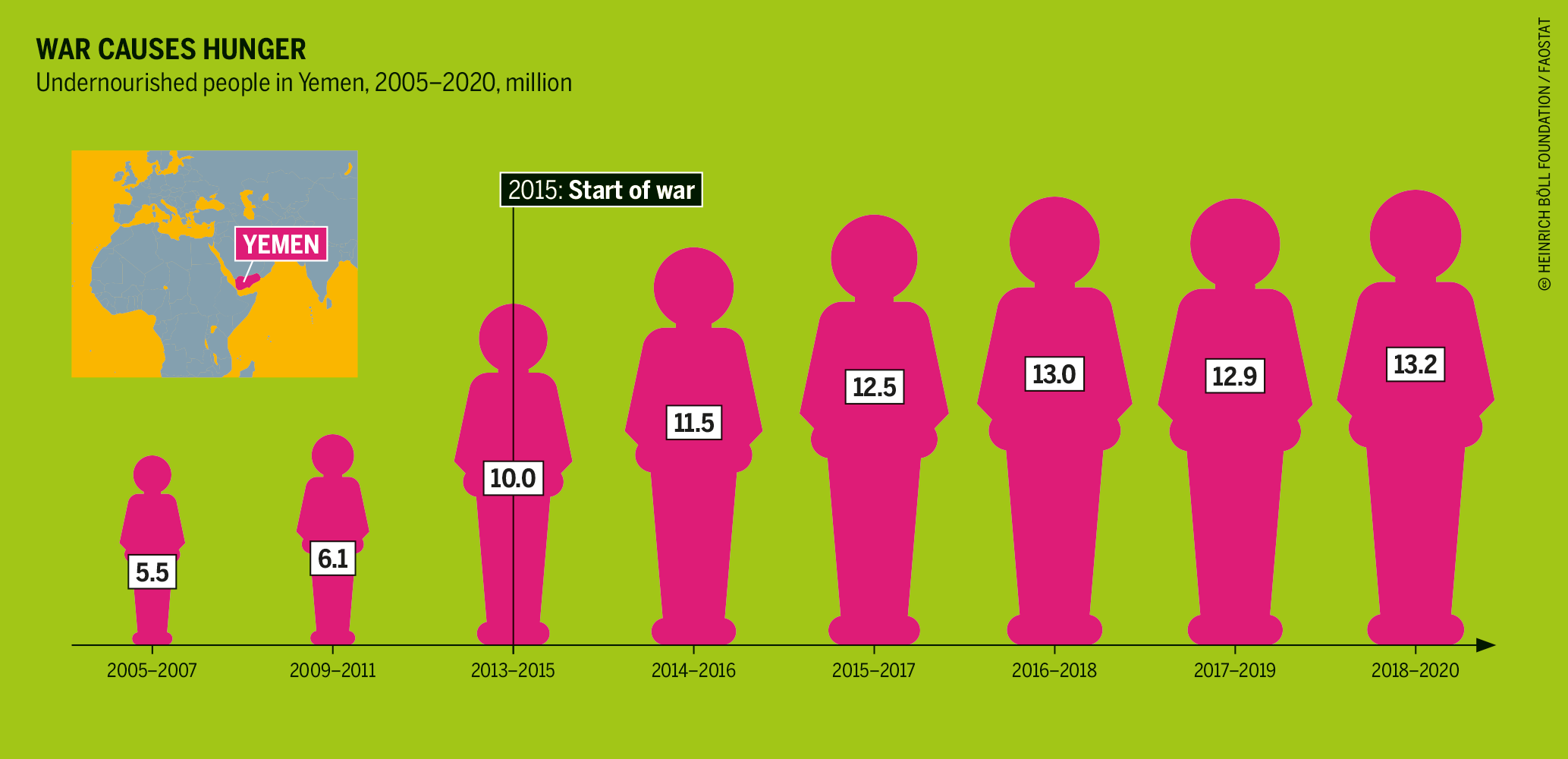

Violent conflicts are one of the main causes of malnutrition worldwide. In 2019, conflicts were the trigger for six of the ten worst food crises. And all countries that experienced famine in 2020 were affected by violent conflict. In Africa, these were Burkina Faso, Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan and Sudan; in the Middle East, Iraq, Palestine, Syria and Yemen; in Central Asia, Afghanistan and conflict regions in Bangladesh and Pakistan. While most countries have made gains in the last 25 years in the fight against hunger and undernutrition, the situation has stagnated in countries affected by conflict, and in some places it has got worse. This is worrying because the number of conflicts worldwide is increasing.

Civil wars and internal conflicts now play a bigger role than wars between states. More than half of the people affected by wars and civil conflicts live in rural areas. Conflicts disrupt all aspects of agriculture, from production to marketing and rural services. Conflicts have both immediate and long-term consequences for agriculture and so for the food security of the population. In conflict regions, crops are destroyed, livestock are stolen and people are driven off their land. The example of the Central African Republic shows some possible long-term consequences. In 2013, armed militias and rebel groups sparked a civil war that continues to this day. By 2015, cereal production was 128,000 tonnes, 70 percent below pre-conflict levels. In 2018 the harvest was only marginally higher, at 134,000 tonnes.

The ways conflicts affect food security and agriculture depend on the local situation. The effects may be direct, and indeed may be a deliberate aspect of military strategy or war tactics. This is the case in Yemen, or in the Ethiopian region of Tigray. Production infrastructure and livestock in these locations are being deliberately targeted, local people are put under siege, their movements are restricted, and they starve. In other conflicts, hunger is an unintended but structural consequence of war, for example when the fighting leads to displacement and destroys livelihoods, food systems and markets. These can push food prices up and reduce the purchasing power of households.

The situation of people who are forced to leave their homes or their country because of conflict is especially menacing. Displaced people are among the most vulnerable populations in the world; they frequently suffer from food insecurity and undernourishment. An estimated 80 percent of those who are displaced by conflict live in countries where people struggle to feed themselves adequately. The number of those displaced by conflict and violence has risen continuously since 2011. By the end of 2019 it had reached a record level of 79.5 million people – almost twice as many as in 2010.

Displaced people cannot cultivate their own land and find it hard to get jobs, and so have virtually no way to provide for themselves. They may remain dependent for years on assistance from governments or aid agencies. Their position is made much worse by rising global food prices. In many places, prices have again reached levels similar to those seen during the food crisis of 2008–9.

Hunger can also give rise to conflict, for example over access to land and water. An example is the weather-related changes in migration routes that pastoralists use, as in the drought years 2015–2017. Rising food prices may also reinforce the perception of injustice against the state when sufficient food is available but poorer sections of society do not have enough money to buy it. The bread riots in 2008 in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Egypt, Haiti and Indonesia are examples of this.

It is not just – or even mainly – a question of producing enough food to fight hunger. Hungry people must have access to healthy food. For this, they depend on an environment in which they can produce enough food themselves, or earn enough money to buy it, and in which they are cushioned in the event of an emergency. Conflicts destroy or undermine the basis of such a long-term strategy to achieve food-security.

Malnutrition

Going hungry, and too much of the wrong things

Malnutrition is increasing worldwide. Too little food inhibits early childhood development, while too many empty calories from sugar and fat may cause cardiovascular diseases or diabetes.

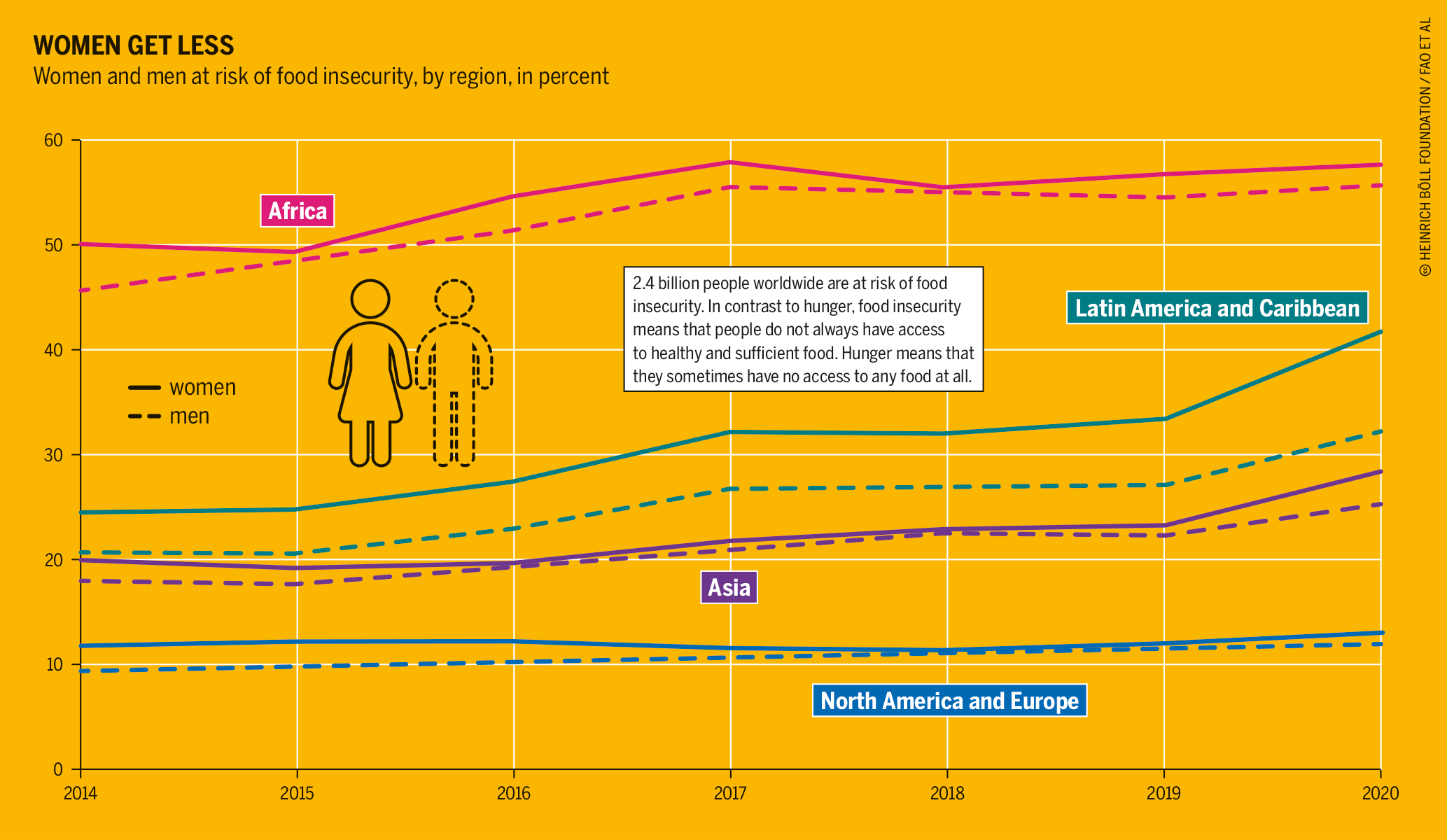

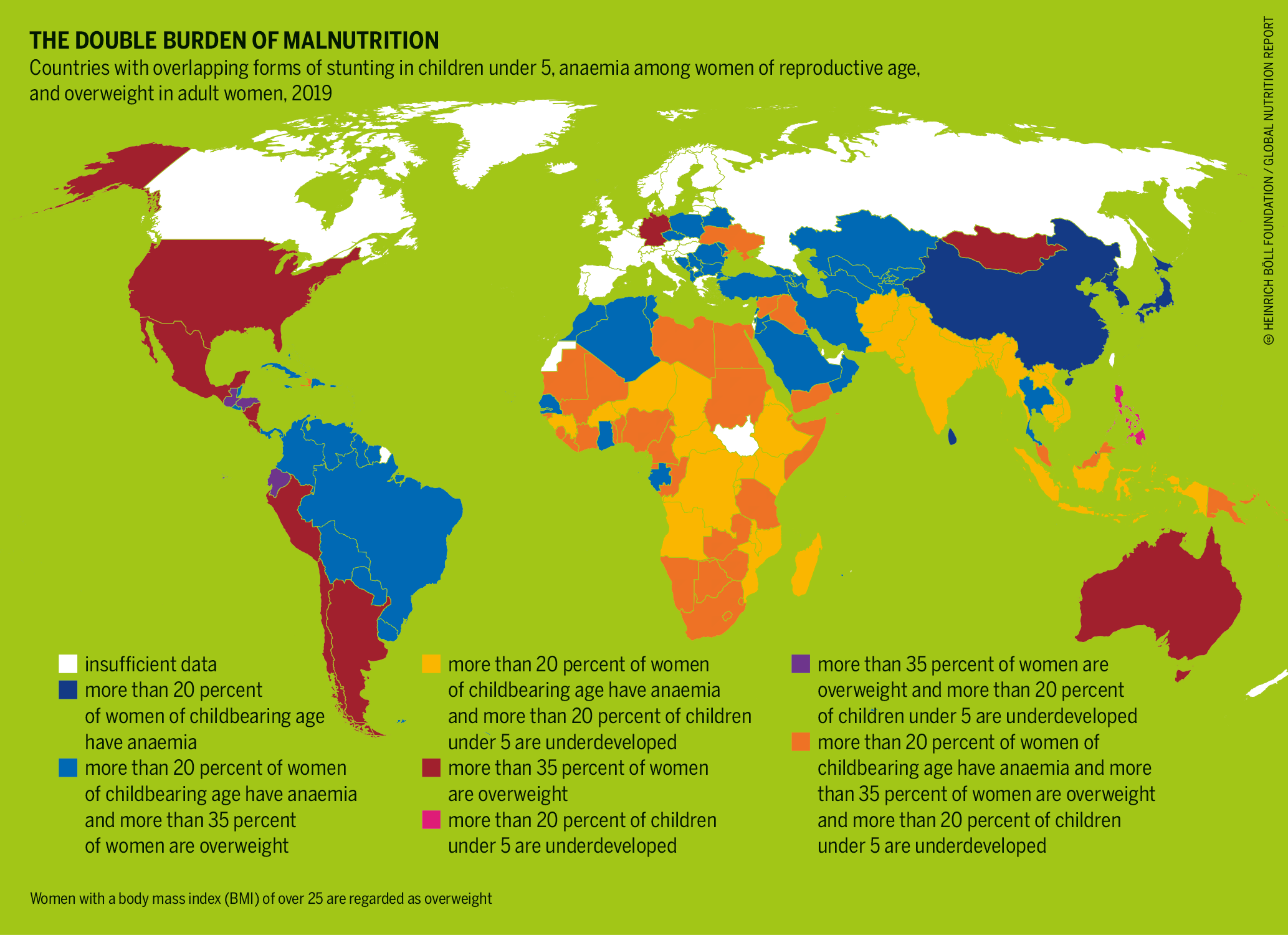

More than one-third of all humanity suffers from some form of malnutrition. That includes both people who are undernourished and who do not consume enough vitamins and minerals, and those who are overweight and obese. Obesity is not a problem of aesthetics, and it does not necessarily make someone ill. But it does increase the risk of particular diseases. Between 2005 and 2014, the number of hungry and undernourished people declined as a proportion of the world’s population. But since 2017 it has increased significantly, and in 2020, some 768 million people were undernourished. At the same time, the number of overweight people is also increasing. In 2018, 1.9 billion adults were classified as overweight or obese. In the Global South, the number of overweight and obese children is growing faster than in the Global North. These countries face the double burden of malnutrition – undernourishment among some, accompanied by overweight and obesity among others.

Hunger particularly affects the development of children. Some 45.4 million children under the age of 5 (6.7 percent of all children) are “wasted” as a result of chronic undernourishment: they are too light for their height. Another 149.2 million, or 22 percent, of boys and girls are “stunted”: they are too short for their age. Some 45 percent of deaths among children under the age of 5 are attributed to undernourishment. Hunger is not confined to the Global South; it also occurs in the Global North. In 2019, 35.2 million Americans lived in households that sometimes did not have enough money to buy adequate food for themselves.

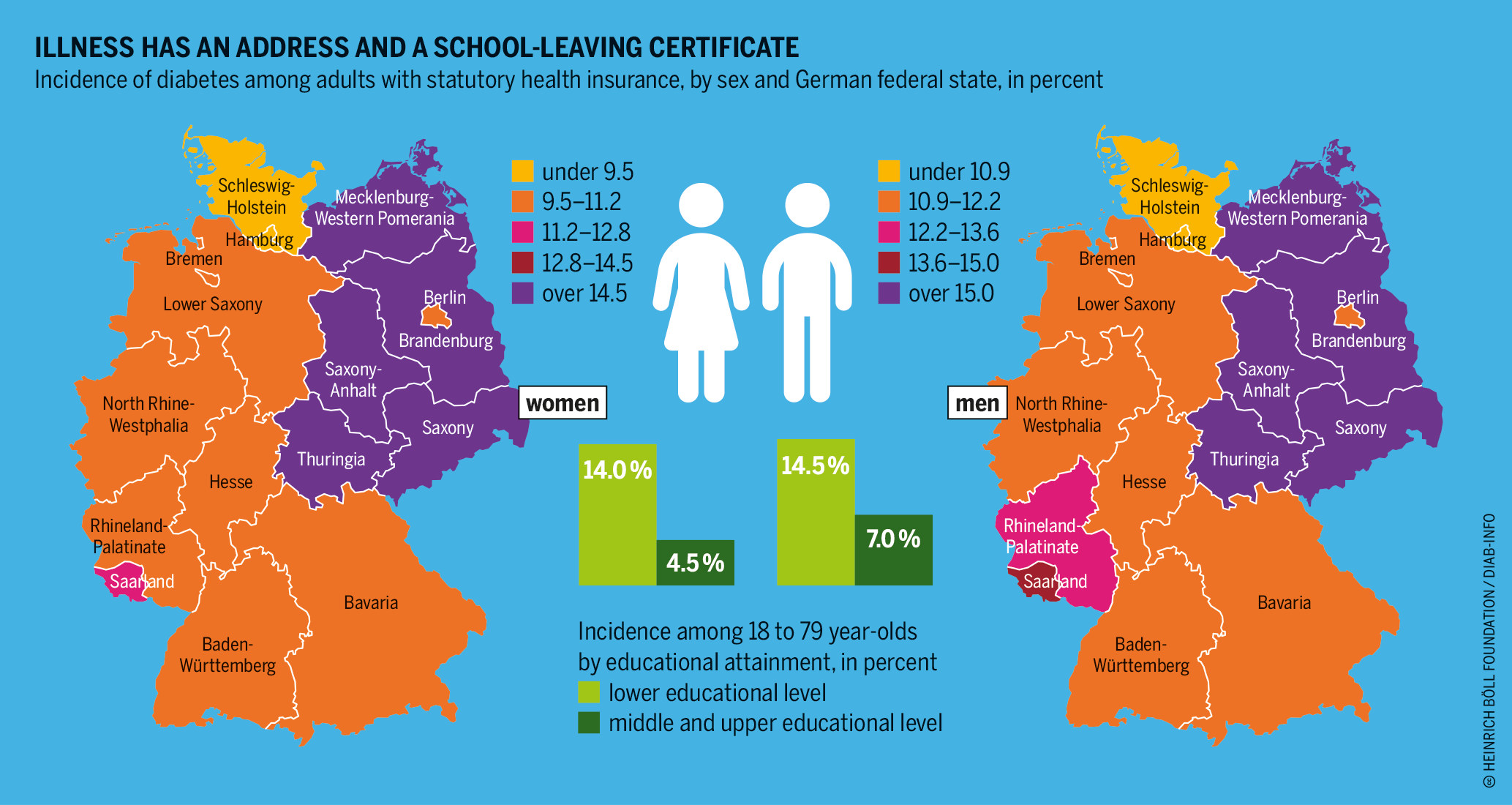

Obesity can make you ill. In the last 20 years, the incidence of non-communicable diseases that may be triggered by poor nutrition, among other things, has increased dramatically. In 2000, some 900,000 people worldwide died of diabetes; in 2019 it was 1.4 million. In 2019, heart disease and strokes were the most common illnesses worldwide. In 2020, they caused 15 million deaths; in 2000 the figure was just 12 million. The causes of overweight and obesity are complex. They result especially from changes in lifestyles and eating habits, combined with too little exercise.

The food crisis of 2008 illustrates how the increased consumption of highly processed foods can have structural causes. Women had to devote more time to earning money to feed their families, at the same time as bearing the bulk of responsibility for care work. In many countries it is mainly women who are responsible for preparing meals. Because they were left with too little time, they tended to buy highly processed food that is easy and quick to cook. Sales of such foods rose, along with the number of people who consumed fast food or ate in snack bars. As a result, the consumption of processed foods with high sugar and salt content rose.

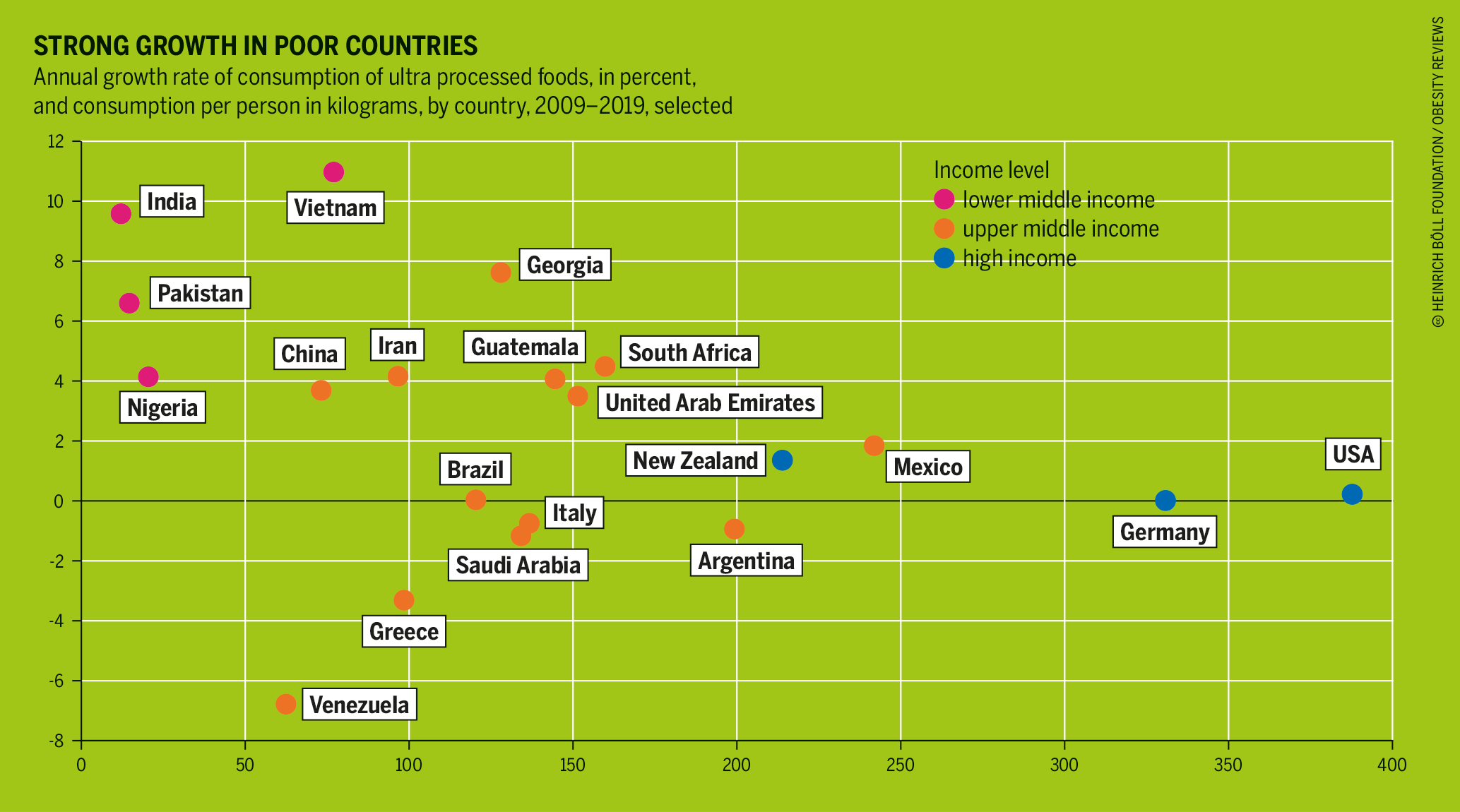

The consumption of ultra-processed foods has come into focus as a cause of obesity. Such foods include sweetened drinks, snacks and frozen meals. They have a high calorie density and often contain cheap ingredients such as palm oil, sugar and starch. They have become part of the food system all over the world. Compared to other foods, ultra-processed items have a longer shelf-life, are more often ready to eat, and are more heavily marketed.

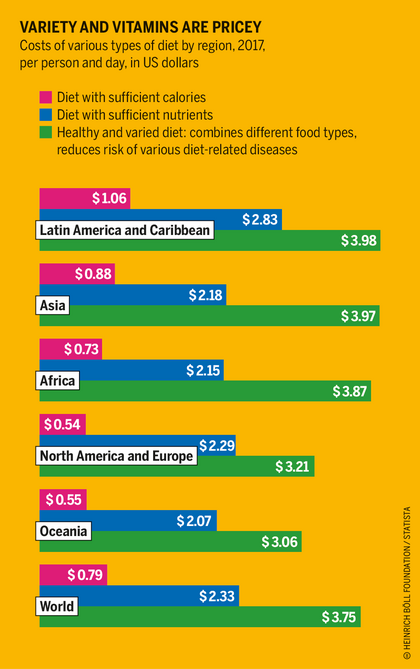

Despite their negative nutritional balance, between 25 and 60 percent of calorie needs (depending on the region) are satisfied from such foods. Market data show that sales of ultra-processed foods have grown fastest in south and southeast Asia, north Africa and the Middle East. Sales of highly processed beverages have grown most strongly in south and southeast Asia and in Africa. A healthy diet is a varied and nutritious diet. But such a diet is five times more expensive than one that merely supplies a person’s energy requirements through starchy staples.

Around the world, 3 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet. On a global average, it costs 79 US cents to supply a person with an adequate number of calories. It costs 2.33 US dollars to provide the same person with a diet that takes into his or her nutritional needs apart from calories. A healthy and varied diet that combines various types of food and that prevents deficiency symptoms and long-term nutrition-related diseases costs at least 3.75 US dollars per person per day. According to a United Nations report, only half of the world’s population can afford a healthy diet that would prevent malnutrition.

Power

Food business, big business

From land ownership to seed supply to food retailing: food value chains are marked by their concentration in a few hands. The imbalance of power between large companies, smallholders and consumers results in malnutrition.

The agriculture and food sector is marked by big differences in power all the way along the value chain. In global markets and at local and regional levels alike, access to land, seeds, water and agricultural services are very unequally distributed. Economic power reinforces political power. As a result, policies designed by and for the elites perpetuate poverty for parts of the population and drive crises such as climate change and species extinction.

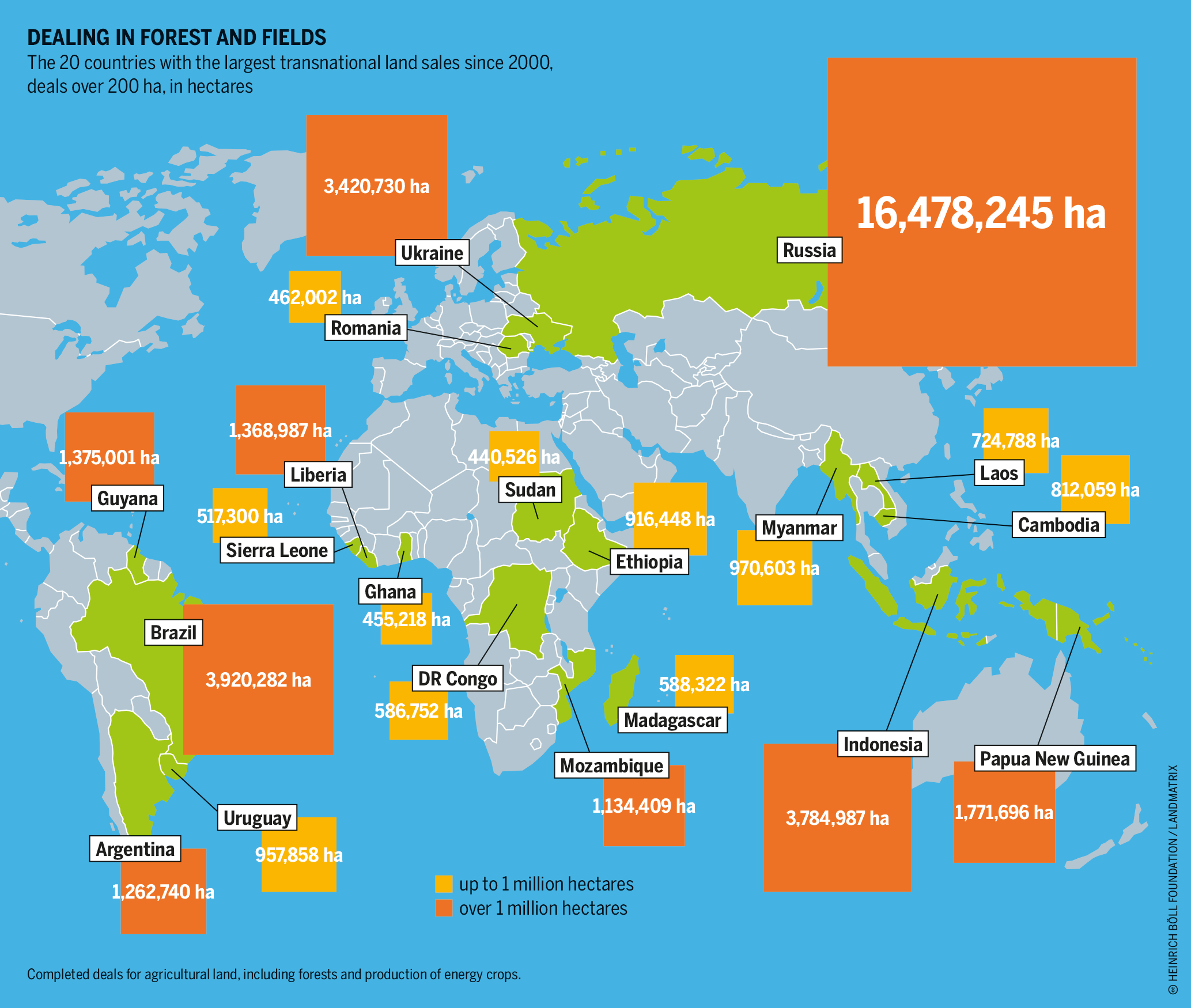

An example of this inequality is the politics around access to land. Many countries around the world have land policies to protect the land rights of vulnerable groups. Yet, implementation is lacking. This is a central issue for food security, as 80 percent of those suffering from extreme poverty live in rural areas. Agriculture is their main source of income; many are subsistence farmers. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that of the 608 million farms worldwide, 84 percent manage less than 2 hectares. Only 1 percent of farm enterprises operate more than 50 hectares. If people are driven from their land, they also lose their livelihoods. The International Land Coalition reckons that inequality in land ownership has been on the rise since the 1980s. In Africa, 10 million hectares of land were acquired for large-scale agriculture between 2000 and 2016. Only about half the land purchased in such deals are now productive farms. Hunger and poverty are more common around the large farms than in areas dominated by smallholdings.

The imbalance is even more severe when the distribution of land between men and women is taken into consideration. In the Global South, only between 10 and 20 percent of landowners are women. In half of all countries worldwide it is difficult or impossible for women to own land. Yet women’s rights to land and property are central aspects of their ability to participate in economic life, produce food and earn an income.

Access to seeds is key for food security. Yet, the economic interests of large seed corporations curb access to seeds. Around 50 percent of the market for commercial seeds is controlled by just four corporations. These include Bayer Crop Science (which includes Monsanto), the American firm Corteva Agriscience, ChemChina/Syngenta, and the French firm Vimorin & Cie/Limagrain. Civil society organizations have long criticized the attempts by big seed companies to influence politics in the Global South to further expand their share in the countries’ seed markets. Among other things, these companies want laws to be changed to reduce farmers’ freedom to propagate, trade or exchange seed themselves. If the farmers were to follow the advice of extension services and buy hybrid seed, they would no longer be able to produce their own seed. That could lead them into a spiral of debt. Aside from that, the huge diversity of traditional seed varieties increases the possibility of meeting the challenges of a changing climate.

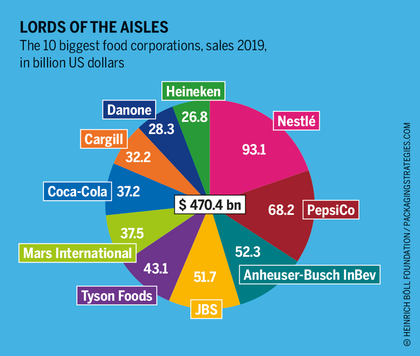

A market concentration with especially negative consequences for health can be seen in food processing. In 2019, five of the biggest food processing companies in the world, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Anheuser-Busch InBev and the meat producers JBS und Tyson Foods, each had sales of more than 40 billion US dollars. These five companies controlled 23 percent of the market share of the top 100 food processing companies worldwide. Their combined sales of 308 billion dollars a year was higher than the gross domestic product of Finland. These food giants use their political clout to maintain their market shares. This was made clear in 2016, in what came to be known as the “Coke Leaks” – a series of emails between two former senior managers at Coca-Cola. These suggest that research results that would suit industry interests should be generated by commissioned studies on the causes of obesity.

Corporate Observatory Europe, a civil society organization, calculates that the food industry in Europe has spent over 500 million euros to lobby against the introduction of Nutri-Scores, a nutritional rating scheme for display on food packaging. The corporations proposed their own, voluntary scheme with far less informative value, and commissioned a think tank which was financed by them to conduct scientific studies on it. These studies were supposed to increase the credibility of their own labelling scheme. The global growth in consumption of ultra-processed food, which results in ever-higher social costs, is also a result of these lobbying activities.

Food poverty

You might not choose the food you eat

In a wealthy country like Germany, can everyone get enough healthy food? It’s not that simple. Income, education and employment are closely linked to health.

The concept of “food poverty” refers to the structural relationships between socioeconomic status, diet and health. Regular surveys on this topic are lacking in Germany, as access to food is regarded as relatively secure. The supply of food has never been greater, food prices have never been lower, and expenditure on food as a proportion of total consumption by private households has never been smaller. The constitutionally guaranteed basic security system is supposed to enable everyone to participate in society. Under these circumstances, if someone eats poorly, this must be the result of a lack of information, ability or other priorities. At least, that is the usual assumption in public discussion.

But social epidemiological research points at the major influence that structural and material conditions can have on behaviour related to nutrition and health. Factors such as the amount of income that the household has at its disposal, the relative price of food, and housing, work and living conditions have a big influence on people’s nutrition and health behaviour – and that is especially true for households with little money at their disposal. The Robert Koch Institute, the government organization responsible for disease prevention and control, calculates that a woman in the highest income bracket can expect to live 8.4 years longer than one in the lowest bracket. For men, the figure is 10.8 years.

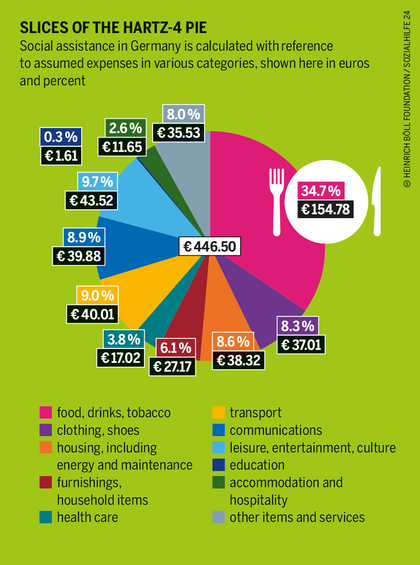

Poverty is a health risk. Someone is regarded as at risk of poverty if their income is less than 60 percent of the national median. In March 2020, 6.48 million people in Germany lived off unemployment or Hartz-IV social security benefits, including 1.87 million children and young people. For adults living alone, the basic monthly benefit in 2020 was 432 euros. That included a food allowance of 150 euros a month, or about 5 euros a day. To make ends meet, poor households tend to buy less food, or food of low quality.

The relationship between food prices and their energy density or nutritional value is little studied in Germany. But research in other wealthy countries show that energy-rich foods high in starch or sugar are relatively cheap compared to healthier fare such as fruits and vegetables, fish or lean meat. Soft drinks, bread, pasta and pizza contain a lot of calories per euro, while fruit and vegetables are relatively expensive. In terms of calorie content, only fats and sugar are cheaper than starchy staples in affluent countries.

Research shows that poor households have a significantly smaller variety of foodstuffs than wealthier households, and that they prefer cheap, filling foods over fruit and vegetables. A total of 11 percent of German households in the lowest income groups say that they cannot afford a full meal every other day. Qualitative studies of nutrition behaviour of poor households, such as one undertaken in the central German city of Giessen, point to financial bottlenecks – mainly at the end of the month – when there is not enough money to pay for a healthy diet. At such times, people have to stretch their budgets or tighten their belts, so they end up with very monotonous meals. Some talk about having to go hungry.

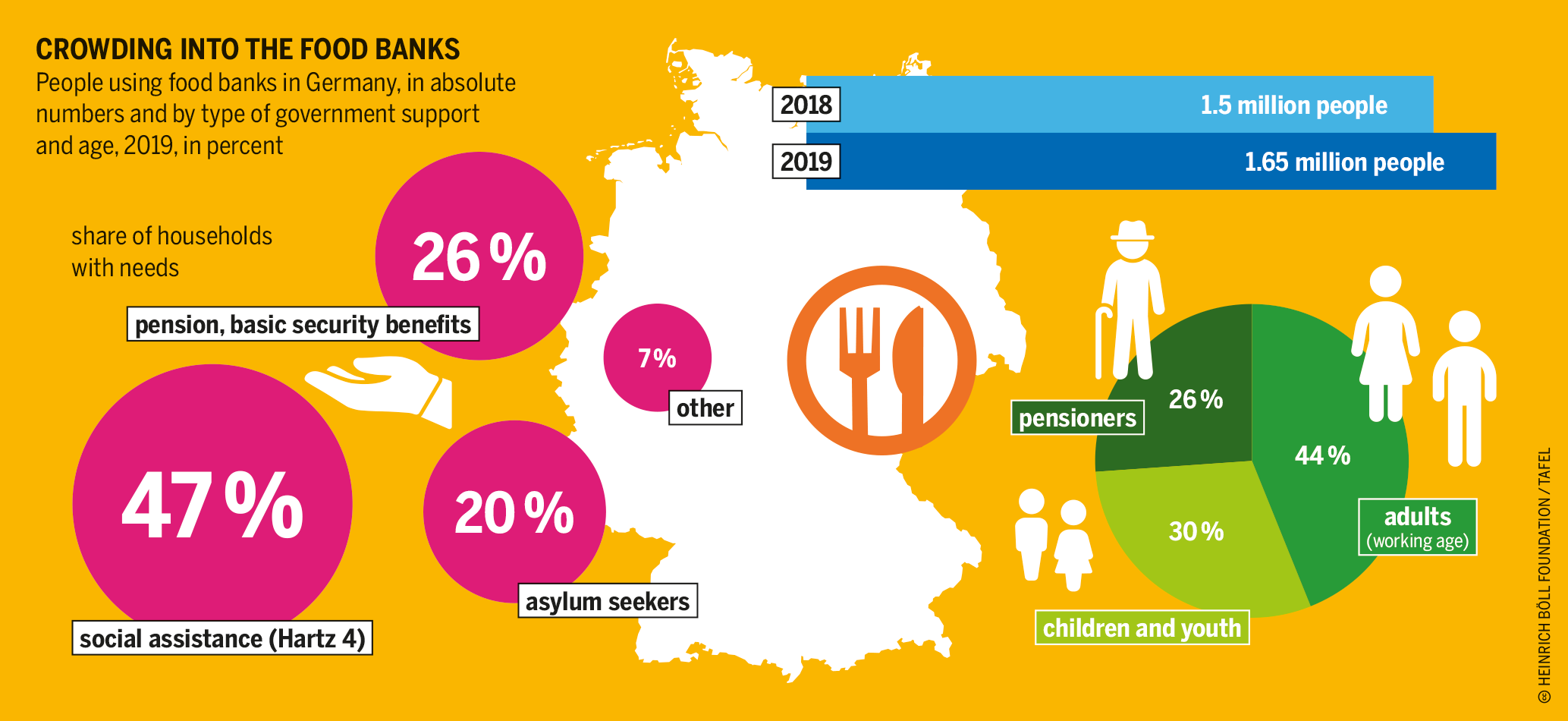

These findings are in line with the first studies of clients of the food banks that are becoming increasingly common in Germany. The food banks distribute unsellable, donated food to needy people in return for a small contribution towards their expenses. In 2019, 1.65 million people took advantage of such services. Most were people who were living off basic social security, followed by pensioners and asylum seekers. In a single year from 2018 to 2019, the number of food-bank clients rose by 10 percent. Half of the 1,033 clients who were questioned in one study said that they could not afford a healthy, nutritious diet. Around 60 percent mentioned they had an unhealthy diet, and around 10 percent reported that they had gone without any food at all at least once in the previous 12 months because they did not have enough money.

Nutrition is important not just for a person’s health. It also has social and cultural functions. Living in poverty can limit people’s ability to participate in everyday routines such as visiting restaurants or canteens or sharing a family meal. This may restrict their involvement in social networks. Children and young people especially suffer from the psychological impacts, such as low self-esteem and limited appreciation of others.

SOURCES FOR DATA AND GRAPHICS

CRISES

A FUTURE WITHOUT HUNGER

www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/cb4474en.pdf, S. 22

www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/cb4474en.pdf, S. 12

WAR

CONFLICTS FEED HUNGER, HUNGER FEEDS CONFLICT

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GRFC%202021%20050521%20med.pdf, p. 252,

www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FS, Abfrage Jemen

https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000125170/download/?_ga=2.83818706.571675159.1625845483-622318131.1610459162

MALNUTRITION

GOING HUNGRY, AND TOO MUCH OF THE WRONG THINGS

https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1195334/umfrage/kosten-fuer-gesunde-ernaehrungweltweit-pro-kopf

https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2020-global-nutrition-report

www.packagingstrategies.com/articles/95613-top-100-food-and-beverage-packaging-companies

POWER

FOOD BUSINESS, BIG BUSINESS

Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, et al.: Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obesity Reviews. 2020,

https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13126

https://landmatrix.org/list/deals

FOOD POVERTY

YOU MIGHT NOT CHOOSE THE FOOD YOU EAT

www.diabinfo.de/zahlen-und-fakten.html

www.tafel.de/fileadmin/media/Presse/Hintergrundinformationen/2019-11-05_Faktenblaetter_gesamt.pdf

www.sozialhilfe24.de/hartz-4-alg-2/regelsatz

Download

Factsheet "Power Poverty Hunger - Food system facts 2021" in english

Factsheet "Armut macht Hunger - Fakten zur globalen Ernährung 2021" in deutscher Sprache

HEINRICH BÖLL FOUNDATION

Fostering democracy and upholding human rights, taking action to prevent the destruction of the global ecosystem, advancing equality between women and men, securing peace through confl ict prevention in crisis zones, and defending the freedom of individuals against excessive state and economic power – these are the objectives that drive the ideas and actions of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. We maintain close ties to the German Green Party (Alliance 90/The Greens) and as a think tank for green visions, we are part of an international network encompassing over 160 partner projects in approximately 60 countries. We maintain a worldwide network with currently 34 international offi ces. The Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Study Program considers itself a workshop for the future; its activities include providing support to especially talented students and academicians, promoting theoretical work of sociopolitical relevance.

Heinrich Böll Foundation

Schumannstr. 8, 10117 Berlin, Germany, www.boell.de

TMG RESEARCH

TMG Research is a not-for-profi t think tank based in Berlin and Nairobi. Together with our partners, we shape transformation processes in order to contribute to a world characterized

by social inclusion and the respect for planetary boundaries. The implementation of human rights, the fi ght against hunger and poverty, and the protection of the climate and biodiversity are the focus of our work. Science with society is our central methodological principle. The world community has set itself ambitious goals for protecting the climate and for sustainable development. Not enough actual progress has been made towards these goals. This is where TMG Research comes in: our applied research aims to support decision-makers in concrete transformation processes. Our partners are civil society organizations and international organizations, ministries and companies. We work in 11 countries on fi ve continents. TMG

Research is a member of the Think Sustainable Europe network.

TMG Research gGmbH

EUREF Campus 6-9, 10829 Berlin, Germany, www.tmg-thinktank.com