Supply chains: “The EU’s general principle is to support, not to punish”

Aside from the German Federal government, EU institutions are also encouraging the introduction of a supply chain law. What would be the consequences? How do the approaches differ, and what does this have to do with the EU’s trade policy? Questions for Bettina Rudloff of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP).

Dr Rudloff, the EU Commission intends to restructure supply chain regulations between Europe and the rest of the world. How will the Commission’s proposal be different from the German proposed legislation?

The Commission wants to primarily reform supply chains to include more protection of human rights and the environment. While Berlin is focusing on human rights, Brussels is including more environmental aspects. Moreover, obligations are being imposed on companies of different sizes than before, and different approaches are being suggested regarding what measures should be taken in the event of violations. Above all, however, the EU approaches apply to all European companies, so there will be no competitive disadvantages for German businesses. In fact, it’s not just about the one EU suggestion, but about two plans: Apart from the proposal regarding human rights obligations, the EU has another proposal to minimise deforestation and forest degradation in EUsupply chains; this is particularly relevant for agriculture.

Why does the EU not simply impose an import stop when countries violate human rights?

Something like that already exists, in the environmental sector as well, in the form of the EU customs system for imports from developing countries. Severe human rights violations are sanctioned with customs disadvantages, as was the case in the past with Myanmar, Belarus, Sri Lanka and recently Cambodia, for example. These countries lost their duty-free market access. In such cases, it’s not a single product or company that’s being punished, but an entire country.

And this system is not enough?

It only applies to developing countries. Also, it is not a suitable tool for constructively promoting implementation. The current proposals on due diligence obligations are different. Before imposing penalties on companies as a last resort, the goal is asking: How can the situation be remedied, how can you motivate businesses and all links in the supply chain all the way to the primary producers to comply with human rights and environmental regulations? Such support ideas also exist for sustainability clauses in EU trade agreements. In addition, the supply chain regulations are intended to empower those affected by human rights and environmental law violations to make better use of grievance systems and options for legal recourse.

But there would be penalties, too.

Imposing penalty payments is the very last resort; there are also the options of cutting state subsidies, or excluding companies from bidding on public contracts. But before that happens, there is an appeal to pay attention and create transparency, to apply due diligence and document it. The basic idea is to support all actors involved.

Why do we, in the EU, have hormone-free beef, but there is cocoa in our chocolate that is grown using child labour?

Regarding the issue of hormone-free meat, there has been a long-standing conflict, in which the EU apparently felt it was ultimately worth it to insist on meat imports without hormones, even if it contradicted trade agreements. The EU lost legal disputes brought before the World Trade Organisation (WTO) against the USA and Canada, because at the time it could not prove that hormone-treated meat poses a health hazard. As a result, the EU had to pay 130 million dollars annually in punitive tariffs to the USA and Canada for 15 years. Through bilateral agreements, the EU nevertheless achieved a ban on imports of hormone-treated meat from these countries – in return for lower tariffs. One could also risk a WTO dispute for import bans against child labour. This could prompt general decision arguments to point out ways to deal with the issue using appropriate rules in the future. However, WTO disputes risked over unilateral trade measures must always be approached with caution, because from a geopolitical standpoint it is very important, especially now, to strengthen multilateral regulations. This is why supply chain laws can be a good complement to trade regulations: When sovereign partner states fail to comply with human rights and environmental standards, I am more likely to change their behaviour through the companies in my sovereign territory – by having European companies put pressure on their suppliers, which will cause a ripple effect through the entire chain and into the partner country.

What is the role of the plans for agricultural supply chains?

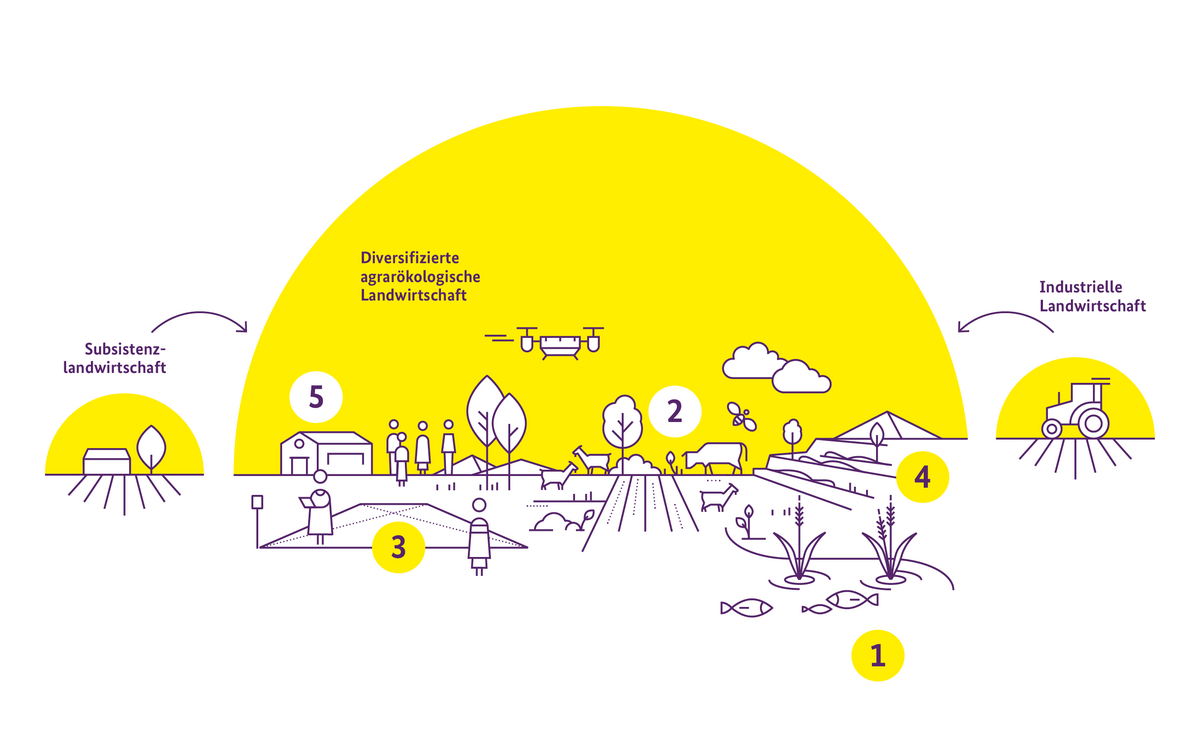

First of all: The due diligence obligations apply to all economic sectors, including the agricultural sector. However, the plans for deforestation-free supply chains affect agriculture in particular. The due diligence requirements are hardly ever aimed directly at agricultural producers. Under the German proposal, they are to apply to companies with 3,000 or, as planned at a later time, 1,000 employees – so more likely the processors or marketers. They incur increased costs due to their management changes and administrative efforts to prove that they are in compliance. This can trickle down to the suppliers, so farmers have to worry that, if they are included in the supply chain, they will have to cope with an even greater administrative burden than they do already. The existing proposals call for lesser requirements for smaller companies. Small producers in developing countries are more likely to have little or no experience with the documentation and certification of their work. They need more time to get accustomed to these processes – and support. Otherwise they drop out of the supply chain and lose income, which is certainly not the purpose of any regulation in defence of human rights.

But due diligence checks should still be required of primary producers?

The proposed regulations should apply to the whole supply chain, particularly with regard to their goal of human rights and environmental protection. But varying levels of responsibility are imposed on the companies, and this responsibility diminishes the further you get from the supplier. There are systems in place already, by the way, which include management assistance for good professional practices and compliance with standards even at the bottom levels of the chain – and in developing countries. After all, better management is generally a good way to prepare for sales opportunities, and then also for implementing sustainability goals. The proposals should therefore be seen more as tools for long-term improvements than just as evil control instruments.

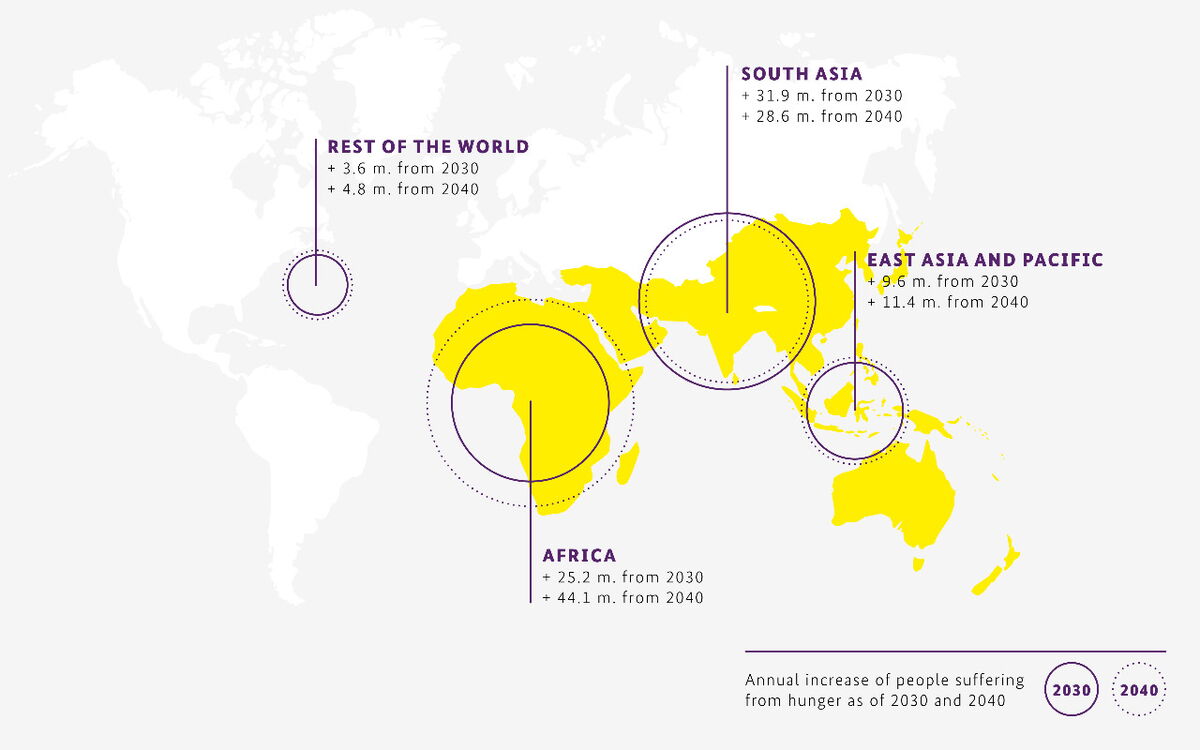

Is it likely that agricultural relationships between European and African countries will decline as a result?

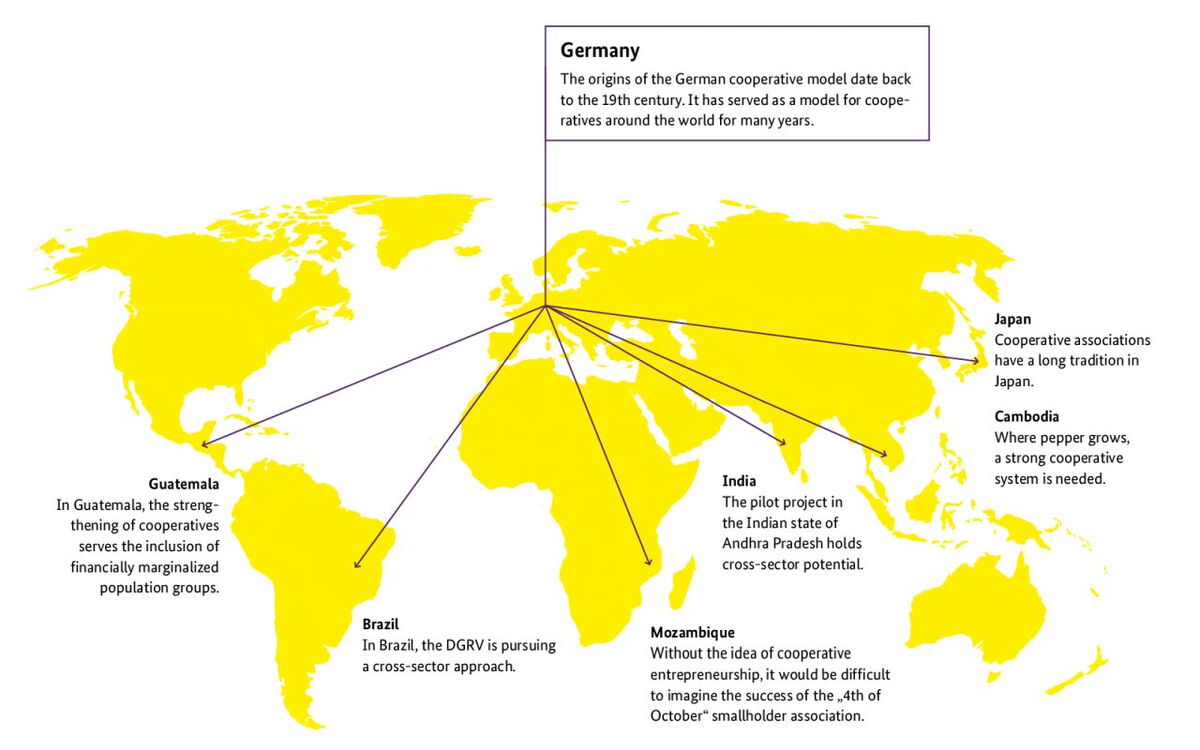

Exports from Africa to the EU have been at a consistent level over the past years, above all tropical fruits, vegetables, flowers and unprocessed commodities like cocoa beans or coffee beans. Not much has happened despite an almost completely open market. The EU opened its market, but this has not resulted in an immense increase in products. Apparently, it is already difficult to get a foothold in the European market – and stricter regulations can make it even more difficult. The important thing will be how these new measures are supported. At the same time, Africans are increasingly looking toward their own continent, for example the efforts to create the African Free Trade Area; and they are also turning toward other trade partners like the Arabian states. The planned due diligence obligations can definitely be a reason for Africans to look around for other trade partners. It all depends on whether and to what extent trade remains attractive – whether sufficient profits are possible despite rising costs, and whether support is offered for complying with these new regulations.

Can you understand the argument that the supply chain law is only being passed to strengthen regional raw materials or products in Germany?

For most of the products currently being imported from Africa to Europe, there is little to no local competition: coffee, cocoa, tea and cotton just come from Africa. For those raw materials, little will change. However, the regional added value of those same products in the producing countries should be strengthened. It’s about building infrastructure and capacities for local processing, and African states themselves are called upon, for example, to lower their energy costs, which are much higher than in the EU in some cases. All supply chain regulations must never lose sight of the fact that they are not merely regulating supply, but should also be concerned with locally added value in developing countries. Processing raw materials in the producing country, however, does not mean that the human rights situation there is better. Support is still possible, for instance through accompanying development policy programmes.

Are there cases in trade law where social or ecological concerns outweighed free trade concerns at the WTO?

The WTO is not working towards the goal of making trade totally free. “Free trade” is still hampered by too many tariffs and by the many exceptions limiting trade – which are due to reasons like health protection. The WTO has had to take these exceptions into account from the beginning, to protect the environment or health, preserve species diversity or to maintain “moral and ethical order”. There have been lots of disputes, like the one about hormone-free meat.

Currently there are three cases that were lost by the states against which the complaints were filed, who had imposed environment-related trade restrictions: Mexican tuna was banned from the US market because fishing techniques were endangering dolphins. Asian shrimp imports were sanctioned at the US border for similar reasons, since catching the shrimp was harming turtles. Although these restrictions were stricken from the law books, they led to different, less harmful fishing techniques for purely economic reasons. In another case, Canadians wanted to create a possibility for the Inuit to sell seal products – as part of their cultural heritage. The EU as the opposing party banned the imports and lost the case. Even though all three cases were lost, it was not due to a lack of consideration for environmental protection. The main criterion for the verdicts was that the rules were implemented in such a way that individual partners were disadvantaged – a general environmental regulation applying to all trade partners would have a better chance to succeed.

What do you think a smart mix would look like?

We already have a mix, but it could be even smarter: Environmental and human rights regulations have existed for states and often for specific sectors for a long time. These are now expanded to apply to companies as a starting point, and for all sectors. Currently, the implementation of all regulations, older ones as well, is especially important: Where problems exist, for example in trade, they must be addressed. The EU has made this one of the strategic goals of its new trade policy, and is taking a cooperative approach to implementation. This is how it should be for supply chain laws as well – by asking local actors who know the local obstacles in detail how best to begin strengthening human rights and improving environmental protection.