Newsletter

Don't miss a thing!

We regularly provide you with the most important news, articles, topics, projects and ideas for One World – No Hunger.

Newsletter

Don't miss a thing!

We regularly provide you with the most important news, articles, topics, projects and ideas for One World – No Hunger.

Please also refer to our data protection declaration.

Hunger figures are rising for the fifth year in a row. The climate crisis and the corona pandemic make 2020 a fateful year in the fight against hunger. Can the goal set by the global community of a "world without hunger" still be achieved by 2030? We asked Miriam Wiemers from Welthungerhilfe about this.

Is the international community still on track in the fight against hunger?

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2020 shows that the world is not on track to meet the international goal of “zero hunger by 2030”. If we continue at our current speed, around 37 countries will not even have reached a low hunger level by 2030.

How have hunger levels developed over the past five years?

The number of people who did not have adequate access to calories declined for many years, however this figure has been increasing since 2015. Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia are particularly affected. But if we also look at the other indicators that the GHI uses, the trends are worrying. 14 countries in the moderate, serious and alarming categories have higher GHI scores compared to 2012. This is often due to a higher number of children who suffer from various forms of hunger, which results in impaired development. This can be seen in wasting (too light for their size, a sign of acute undernutrition) or stunted growth (too small for their age, a sign of chronic undernutrition). Looking back at trends since 2000, hunger worldwide has gradually declined over the last 20 years. Many countries have made huge progress. Sierra Leone, Ethiopia and Angola improved by two GHI categories after conflicts in these countries came to an end. These countries had a score of extremely alarming in 2000, while today, their score is serious. This shows that it is possible to reduce hunger. But there is still a lot of work to do.

Can 2020 be figuratively referred to as the “Plague Year”?

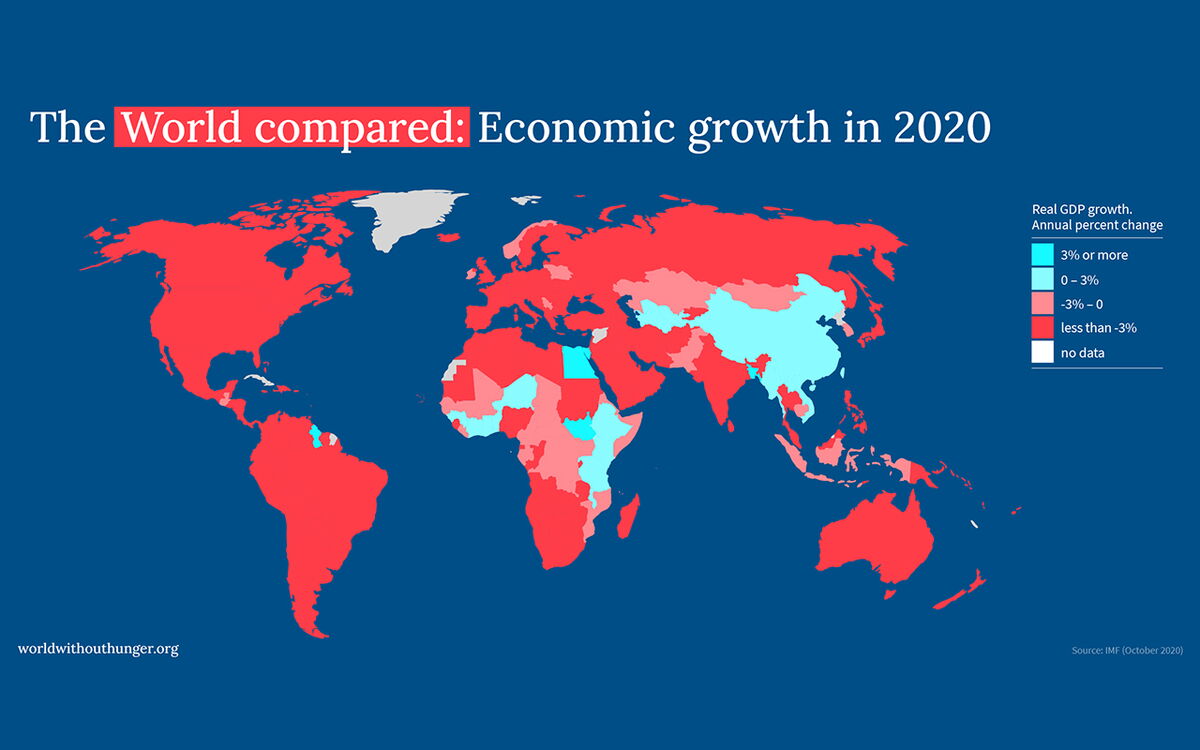

2020 has certainly been an exceptional crisis year. Not only the COVID-19 pandemic, but especially the increase in extreme weather events and economic crises pose huge challenges for us. We are likely to see more of these in the future if we do not take immediate and decisive action. The many crises of 2020 have once again demonstrated that human activity is having a growing negative impact on the planet and not only are we risking the health of animals, plants and our environment but also our own. One cause of new kinds of infectious diseases is the destruction of natural habitats due to land degradation, climate change and the exploitation of resources. This is directly related to our lifestyle and, for example, the greater demand for (intensively produced) animal products as well as non-sustainable agriculture.

What are the risks of the events of 2020 (pandemic, economic crisis, locusts) on the next few years?

The fact that crises are happening in quicker succession poses a huge risk to sustainable development - those affected can no longer recover from a crisis because the next one follows almost immediately or even occurs at the same time. This is strongly linked to the consequences of climate change, which, and this cannot be emphasised enough, can still be slowed down. But the quick succession of the crises is making the work more difficult for us as an organisation that wants to support people in the best possible way to become more resilient. Our first job is to provide humanitarian aid, but we cannot neglect the development projects focussing on sustainability. Sustainable development needs time, but time is not on our side.

The main problem is the extreme inequality within the food systems.

It is difficult to do anything when famine is driven by conflicts. We are open to suggestions.

Unfortunately, conflicts cannot be solved by humanitarian aid organisations or development cooperation. They especially require political and social solutions as well as the will to implement them. We try to have a positive influence on these processes with our political work, but it is also important to react to the crises that occur during these long political as well as social processes - consoling those in need with political solutions does not fill their bellies. It is worth emphasising that this is not some vague moral obligation that we feel – the right to food is a human right. What we can do is increase the resilience to crises. To put it simply, we cannot prevent earthquakes, but we can prepare for the consequences in order to recover more quickly from the crisis. And this also applies to the consequences of climate change and conflicts. We believe our work of strengthening food security also contributes to conflict prevention. While this admittedly appears to be a never-ending and thankless task, doing nothing is not an alternative for us - especially since the GHI also shows encouraging trends as some countries have considerably reduced their levels of hunger. So it is possible.

What are the flaws in our food systems?

The main problem is the extreme inequality within the food systems. On the one hand, the standards for social protection, health and food quality are high in the countries in the Global North, while countries in the Global South are either not or inadequately taken into consideration or even involved. An example: Most high-income countries collaborate internationally to increase the production and income of small-scale farmers in low-income countries, yet they keep their trade benefits by using non-tariff barriers. In the Global North, every aspect of property and ownership structures is regulated, while land grabbing is a widespread problem in countries in the Global South, where land ownership rights are often not secured. This land grabbing results in the displacement of small-scale farmers, livestock herders and indigenous peoples as well as the associated food insecurity and is frequently driven by financial and agricultural corporations. In order to offer a wide and cheap range of foods in the north, some of the low environmental and social standards in countries in the south are exploited. This situation is aggravated by the lack of social security and the destruction of the environment, creating a vicious circle of becoming more dependent on countries in the north and having to make greater concessions to them. Issues such as sustainability are the first thing that goes out the window, resulting in a downward spiral. To stop this, we must restructure our food systems so that they are fair, healthy and environmentally friendly.

How can they be made more resilient?

In order to make our food systems fairer, more sustainable and more resilient to crises, we must address the way we produce, trade and consume food. Taking cocoa as an example, we can see how globalised our food systems are today: Cocoa that is grown on a small-scale farm in Sierra Leone goes through many steps to end up in our shopping baskets as chocolate - often for less than one Euro. How much money do the small-scale farmers receive and how are they meant to use this to secure their food? We need to look at this system more as a whole - then we can see that there are many other key factors. One is sustainable production that does not contribute to land degradation, a loss of biodiversity and climate change. Local and regional value creation and food markets must also be strengthened. Compliance with human rights and environmental standards must be a legal requirements in value creation and along the entire supply chain, which includes a fair income for producers. This may sound very abstract at first, but the following example shows how we and our partner organisations are tackling this topic: Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe launched a joint project to strengthen resilience and improve food security in the Masisi Territory in the DR of Congo. This is a key destination for internally displaced people, where the food system is under pressure. The project aims to improve participants’ agricultural production and nutritional knowledge, access to water, livelihood diversification, and economic empowerment. It helps communities identify and prepare for and prevent potential catastrophes. It also supports smallholder households by providing them with seeds, tools and training, promoting land use planning and improving their marketing strategies. The support in setting up microenterprises or looking for work is targeted to women and young adults. The project is based on close collaboration with local organisations, farming groups, rural families and state institutions in order to build up long-term capacity in the communities. Projects like these illustrate certain areas in which politics and economics should take action to make food systems more resilient.

They demand a One Health approach. What does this involve?

A One Health approach not only helps to show that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment. It also calls for policy-makers to see that these areas are inextricably linked. The current crises have once again demonstrated how important it is to use integrated approaches, collaborate across all sectors and create coherent policies.

Instead of zero, the number of people who are starving could reach 840 million by 2030

What must be changed now?

More than half of the world’s population has no social security in the event of a crisis. Unlike most people here in Germany, they cannot rely on a social security net provided by the state. The multiple current crises are revealing the effects of this. Therefore, expanding social security programs is urgently needed. It must also be ensured that despite the COVID-19 containment measures, people can still access markets and agricultural supplies in order to secure the supply of food. But every one of us here in Germany can contribute today, for example by deciding to put regional, seasonal or fair-trade products in our shopping trollies.

What do you think our review will be in 2030?

The current forecast paints a bleak picture. Instead of zero, the number of people who are starving could reach 840 million by 2030. The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences are likely to dramatically increase undernutrition in children. But the GHI also shows that hunger can be reduced. More than anything, it requires political will, seeing as hunger is a political issue. If measures are implemented, such as targeted investments in a fair food environment for small-scale farmers in rural areas and coherent agricultural, health and trade policies, then we can end hunger by 2030.

Read more Global responsibility: Tackling hunger is the only way forward

Read more Biodiversity and agriculture – rivalry or a new friendship?

Read more Mr. Marí, what happened at the alternative summit?

Read more What is wrong with our nutrition in Germany, Mr. Plagge ?

Read more How Can We Feed The World in Times of Climate Change?

Read more Nine Harvests Left until 2030: How Will the BMZ Organise Itself in the Future?

Read more Cooperation and Effective Incentives for Sustainable Land Use

Read more What Needs to Change for Africa’s Youth, Ms Kah Walla?

Read more How to Enhance Soil Organic Carbon – Uniting Traditional and Innovative Practices

Read more Digitalization: The Driving Force in the Future of Agriculture?

Read more Our Food Systems are in Urgent Need of Crisis-Proofing: what needs to be done

Read more "Human capital will play a pivotal role in the transformation of African economies"

Read more The importance of water for sustainable rural development

Read more New legal initiatives towards deforestation-free supply chains as a game changer

Read more 2022, a year of crisis – What does it mean for African trade and food security?

Read more How the War against Ukraine Destabilizes Global Grain Markets

Read more Controversy: Do supply chains need liability rules?

Read more 5 Questions for Jann Lay: What is Corona doing to the economy?

Read more Sustainable, feminist and socially just: The new Africa strategy of the BMZ

Read more Do import restrictions really benefit the local poor in West Africa?

Read more Sang'alo Institute invests in farming of sunflower crop

Read more Farmers' organizations want to be involved in designing agricultural policy

Read more BMZ releases video on the transformation of agricultural and food systems

Read more “More of the same is not enough - we need to rethink”

Read more Partners for change - Network meeting on transforming agricultural and food systems

Read more What is needed for a long-term fertiliser strategy?

Read more A framework for sustainable and fair agriculture and food systems

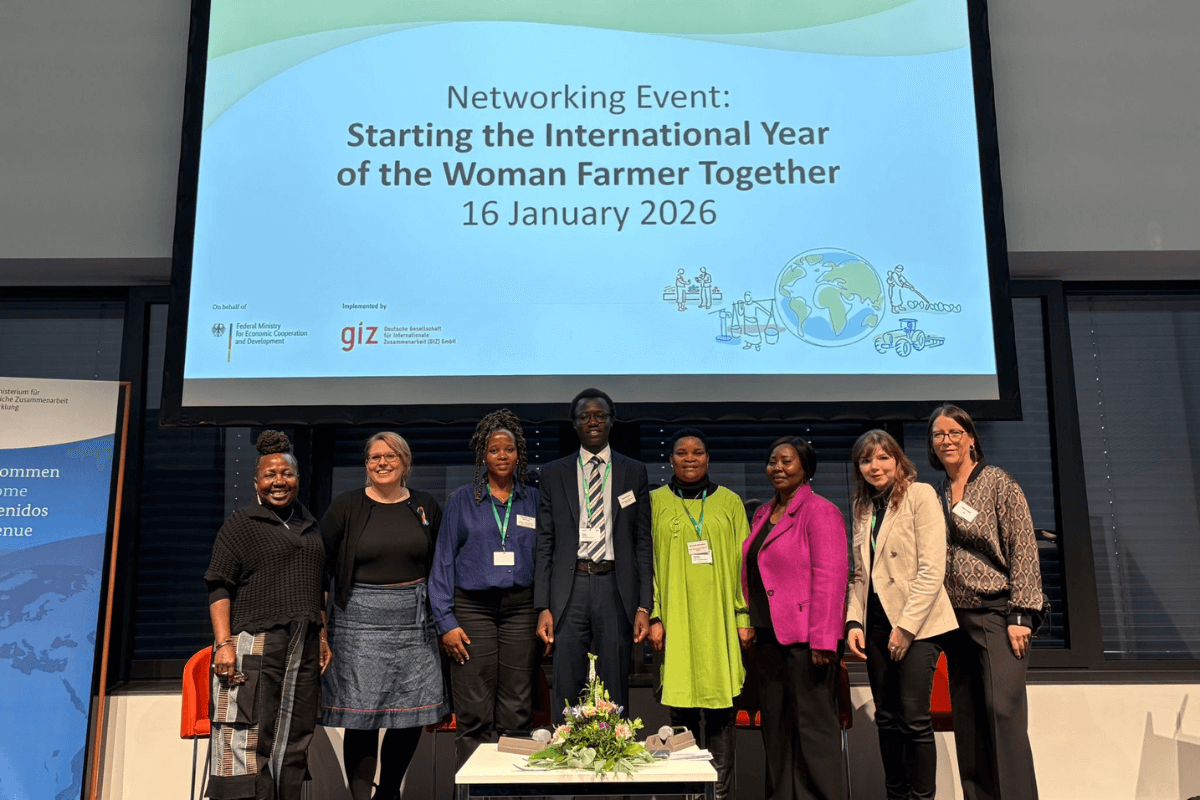

Read more Female Leadership: A Key Lever for Transformation?

Read more Gender-Transformative Approaches – Unlocking Everyone’s Potential

Read more Adapted financial services – a key to transformation

Read more From Pledges to Progress: Nutrition at the Heart of Inclusive Development

Read more A political opportunity to overcome structural barriers for women farmers

Read more Climate Adaptation Summit 2021: ‘We can do better’

Read more Mr. Samimi, what is environmental change doing to Africa?

Read more Resilient small-scale agriculture: A key in global crises

Read more Gender equality: Essential for food and nutrition security

Read more Planetary Health: Recommendations for a Post-Pandemic World

Read more This is how developing countries can adapt better to droughts

Read more The North bears the responsibility, the South bears the burden

Read more A Climate of Hunger: How the Climate Crisis Fuels the Hunger

Read more Innovate2030: Digital Ideas against Urban Climate Change

Read more ‘None of the Three Traffic Light Coalition Parties is Close to the Paris Agreement’

Read more Building Better Resilience to Transboundary Threats

Read more Building climate-resilient and equitable food systems: Why we need agroecology

Read more How are transformation and crisis intervention related, Dr. Frick?

Read more Fair Trade and Climate Justice: Everything is Conntected

Read more COP27: Agri-food systems in the focus of the climate discussion

Read more G7 Sustainable Supply Chains Initiative: From Commitment to Action

Read more Climate, biodiversity and nutrition are inextricably linked

Read more Why biodiversity is important for climate protection & food security - and vice versa

Read more Social justice and climate justice: Fair Vibe at the Youth Climate Conference

Read more CompensACTION aims to reward farmers for climate performance

Read more "Climate change is unifying people from the region"

Read more One Health – What we are learning from the Corona crisis

Read more The state of food security in Cape Town and St. Helena Bay

Read more School Feeding: A unique platform to address gender inequalities

Read more Success story allotment garden: Food supply and women's empowerment

Read more How can the private sector prevent food loss and waste?

Read more Food System Transformation Starts and Ends with Diversity

Read more Agricultural prices and food security – a complex relationship

Read more Video diaries in the days of Corona: Voices from the ground

Read more The hype about urban gardening: farmers or hobby gardeners?

Read more From lost products to safe food - Innovations from Zambia

Read more Mozambique: How informal workers find jobs through an app

Read more Stepping into the future: How youth organisations are driving change

Read more "We have high expectations of the Kampala Declaration"

Read more "The Agri-Sector is a Space of Opportunity and Entrepreneurship"

Read more How much private investment is the agricultural sector able to bear?

Read more Small-scale farmers’ responses to COVID-19 related restrictions

Read more ONE WORLD no hunger - Meet the people driving rural transformation

Read more City, Country, Sea: 6 Innovations in the Fight Against Climate Change

Read more For a just transition to a sustainable planet we must secure land rights

Read more The lessons learned from the last food crisis - A solution?

Read more Food security is more than production volumes and high yields

Read more COVID-19 and Rising Food Prices: What’s Really Happening?

Read more The Rice Sector in West Africa: A Political Challenge

Read more “Corona exposes the weaknesses of our nutritional systems"

Read more 5 questions to F. Patterson: Why is there more hunger?

Read more The Black Sea Breadbasket in Crisis: Facts and Figures

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help to improve your user experience. Your consent is voluntary and can be revoked at any time on the "Privacy" page.

Protects against cross-site request forgery attacks

Saves the current PHP session.

Content from third-party providers, such as YouTube, which collect data about usage. Third-party content embedded on this website will only be displayed to you if you expressly agree to this here.

We use Matomo analytics software, which collects anonymous data about website usage and functionality to improve our website and user experience.