Farmers in revolt-their movement brings unity and hope

India, a newly industrialised country, is ranked between countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda in the World Hunger Index. Since 2014, a law has guaranteed all Indians sufficient healthy food at affordable prices. Now one of the biggest waves of protest in history is rocking the subcontinent. Farmers are fighting back against laws that abolish guaranteed minimum prices and put nutrition programmes in jeopardy.

November is usually a month of pleasant weather and festivals in New Delhi, but in November 2020, events took a different turn. Farmers marched in their thousands towards the Indian capital and were stopped at the city boundaries by a huge police presence. However, the determined farmers refused to be intimidated into submission. They started a dharna (sit-in protest) at various sites. The situation for India's farmers is difficult. They often have to deal with increasing debts, which place their land and livelihood at risk. More than eight out of ten farms are smallholdings on plots of less than two hectares. They are crushed by what is considered the price of the green revolution: steadily and recently sharply rising costs for artificial fertilisers and pesticides to maintain yields on depleted soils.

The overexploitation of nature is compounded by an exploitative environment: in the villages, moneylenders still decide who gets loans and at higher interest rates than in banks. They are also usually the middlemen who buy the fruits of the farmer's labour – at the prices they determine. Three laws passed by the Modi government sparked the protests. The government aims to open up hitherto protected markets for agricultural products.

The impression has grown among the farming community that agricultural development policy is playing into the hands of corporate interests and large farms at the expense of small and medium-sized farms.

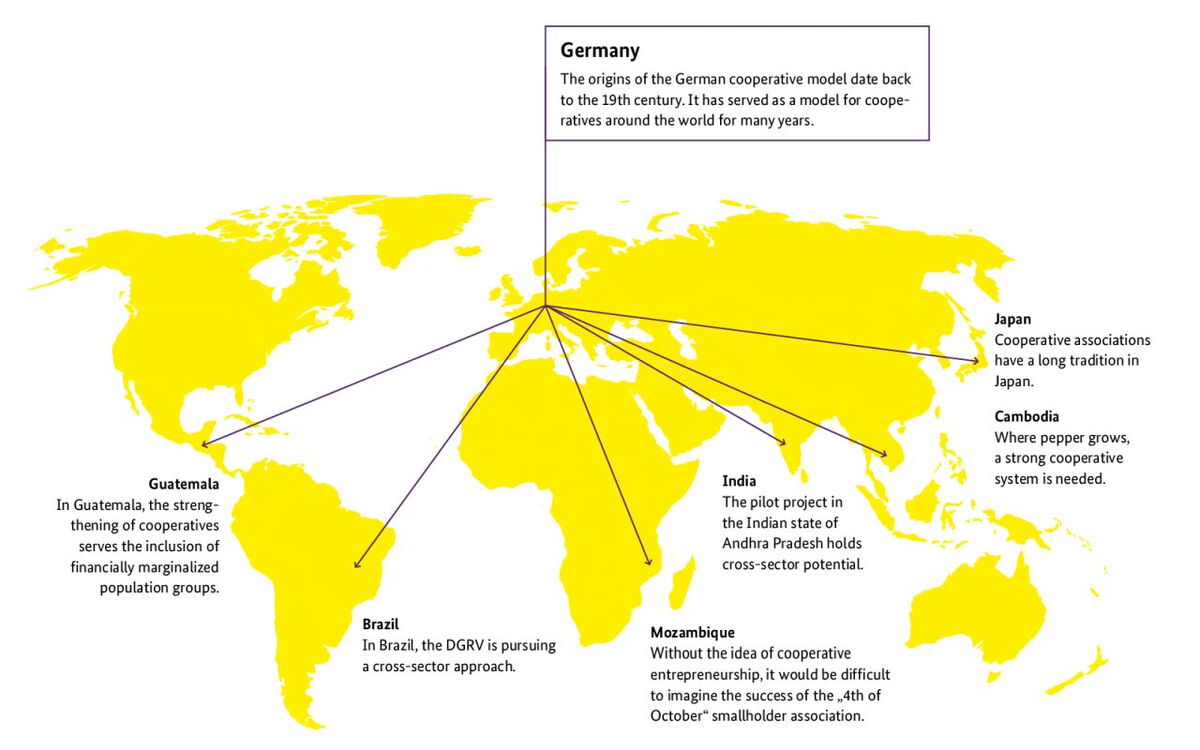

Until now, most Indian farmers sold most of their produce on state-controlled, wholesale markets called mandis – at base or minimum prices that are set centrally for the whole of India before each sowing. The mandis are regulated by the states. Accordingly, in a system of licences, taxes and levies, the sale of agricultural commodities takes place only at these markets, which involve large landowners, large grain traders and sales agents. The three laws now interact to strengthen the market power of the agri-food industry. The first law aims to facilitate contract farming, which is based on agreements. However, farmers fear from experience that they would be forced to buy expensive inputs and receive unfair prices for their produce. Also, large agricultural companies will be able to demand an even higher percentage of the food farmers grow. These will be mainly export or luxury crops instead of diverse staple foods for farmers’ own food security.

The second law provides for a market system without taxes and levies separate to the regulated market. Farmers fear that this will inevitably displace the regulated market. The third change concerns storage – until now also a state domain, with inadequate infrastructure and overflowing grain silos. Large companies will henceforth be able to stockpile staple foods without having to take into account actual demand. Farmers' organisations argue that this will create a new source of profit for companies instead of meeting the basic needs of the population.

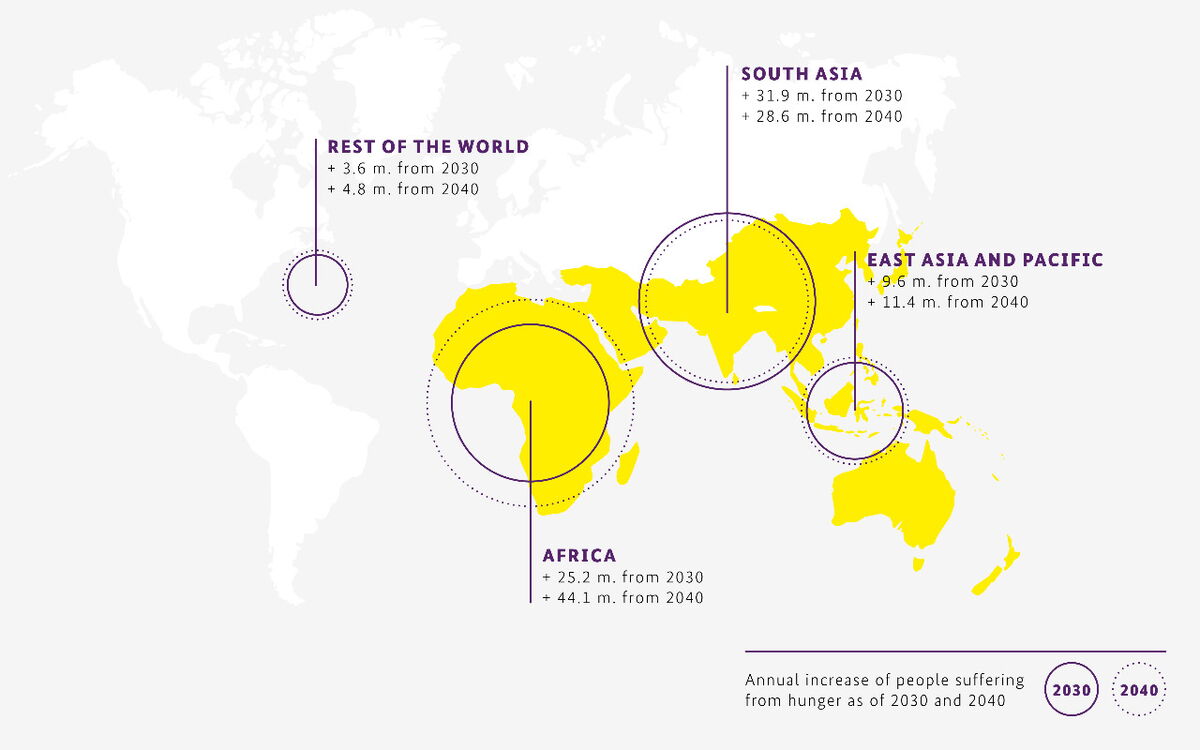

In the fertile areas of Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh a large proportion of farmers depend on the mandi system, but also beyond that, farmers rely on the guaranteed prices. In other respects, too, government procurement of wheat and rice in particular – and to a lesser extent other staple foods – at minimum prices has proved successful. It ensures adequate stocks and allows the government to distribute discounted food rations for vulnerable families below the poverty line. The new laws threaten the continuous supply of food to the poor and malnourished. Experts demand a review of the laws’ content. Well-known activist Medha Patkar also supports the repeal of the laws because they weaken farmers' interests in favour of the agri-food industry. They confirm the fears of the farmers' movement that in the end food security will suffer if large, profit-oriented corporations upset the Public Distribution System.

According to some organisations, there are unofficial talks to at least partially freeze the reform. This is because the farmers' concerns find broad support in various social movements, including the National Alliance of People's Movements (NAPM), as well as some youth, women's and workers' organisations. Thus, the protest is linked to concerns of free food distribution, better cooperation between farmers and workers or overcoming the strict separation of religions, regions and castes. Overall, farmers feel more confident and dare to voice their problems.

However, the movement lacks the necessary commitment to steering Indian agriculture into ecologically sustainable paths.

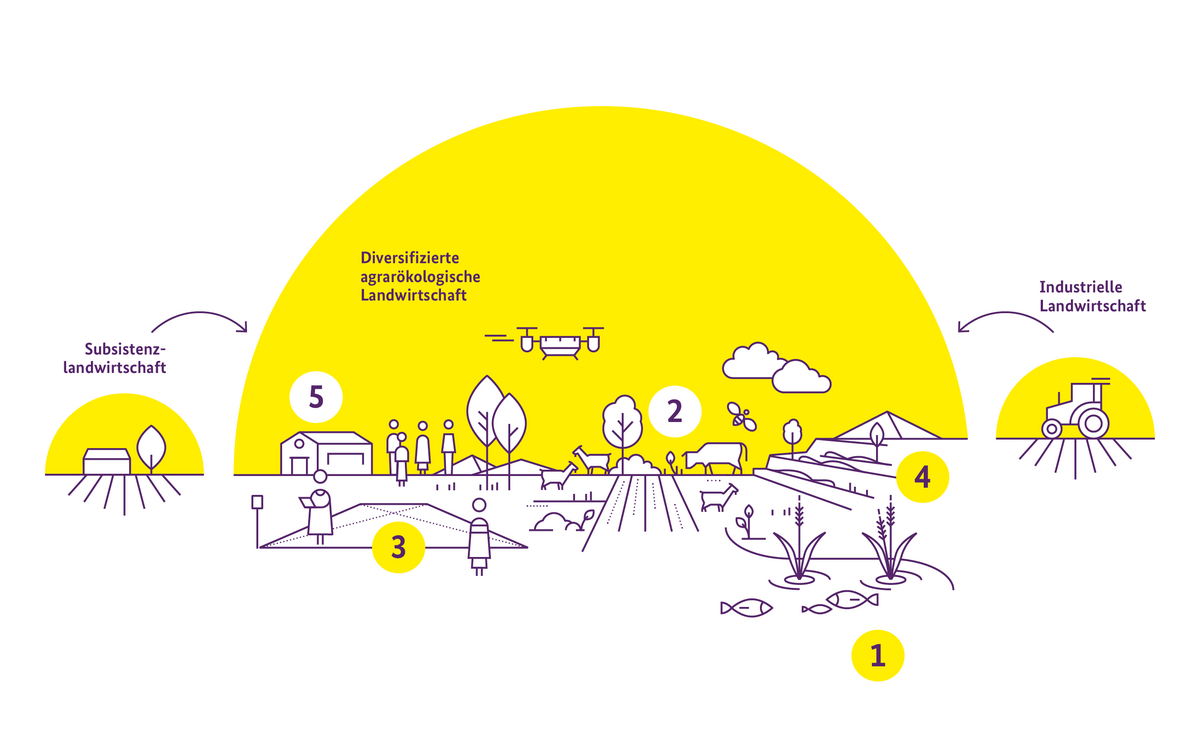

Although this issue is becoming more urgent as the climate crisis intensifies, the protest movement is primarily concerned with getting legal guarantees for a state system of minimum prices. To converge these two goals, the way forward would be to significantly reduce farmers’ costs – especially by decreasing dependency on expensive seeds, chemical fertilisers, pesticides, insecticides, diesel, etc. – while at the same time focusing on ecologically friendly farming methods. As a result, guaranteed prices would be linked to environmentally friendly and sustainable agriculture.

The real challenge, however, is to reconcile environmental concerns with those of wide-scale farmers' poverty and problems of inequality. More than two-thirds of India's population lives in villages, and land is a major source of livelihood. In terms of land ownership, the bottom 50 per cent of rural households account for only about 0.4 per cent. In the late eighties, this number was at four per cent. The top ten per cent of landowners, on the other hand, control 50 per cent of agricultural land. India's agriculture needs a combination of environmental protection, climate change mitigation and adaptation measures, and a rights-based system that also grants some land to smaller farmers and the landless.