Labels, customs tariffs and supply chain legislation: Do they benefit or harm smallholders?

In the discussion about sustainability in supply chains, European states focus on labels, customs tariffs and government regulations such as the Supply Chain Act. Journalist Jan Grossarth, with the support of SEWOH partners, questions whether these measures actually help smallholders.

After the eight-storey Rana Plaza factory collapsed in Bangladesh in April 2013, killing over a thousand textile workers under the rubble, the issue of human rights in sewing factories dominated global news for a few days. The initial shock turned into shame. After all, wasn’t everyone who bought cheap T-shirts and jeans somehow responsible? This was followed by a political debate: Hadn’t the disaster happened in a domain where the state, i.e. Bangladesh, should have ensured compliance with its laws? Or, on the other hand, do we not have a say in the regulations determining how the products we consume are manufactured? Not only through consumption, but through our government and companies?

In Germany, therefore, the disaster triggered a discussion on supply chain legislation. Yet, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) had already adopted the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011. In addition to state protection, a principle was internationally enshrined in this legislation whereby companies, too, should be responsible for enforcing respect for human rights. To ensure this, companies need to apply appropriate due diligence in their supply chains. It was agreed that importers of both primary and industrial products must themselves monitor, be accountable for and demonstrate that their suppliers comply with human rights standards. To meet their duty of care, they must ensure that there is no child labour and that workplaces are safe and humane. In some cases, however, and especially in the textile industry, conditions continue to prevail that could justifiably be called slave labour. The same is true for the extraction and production of raw materials, an industry where working conditions are still unregulated and inhumane in numerous places. Germany initially attempted to implement the UN Guiding Principles on a voluntary basis, however, less than 20 percent of all German companies with over 500 employees subsequently adopted them.

Ten years after agreeing to the international community’s Guiding Principles, the German federal government passed a supply chain law requiring large companies to provide evidence. France and the UK have already introduced legal due diligence requirements, as has the Dutch parliament. Moreover, corporate due diligence standards are also being drafted by the EU, focusing on human rights and environmental sustainability, especially on “deforestation-free supply chains”. In light of this year’s climate negotiations, international attention is increasingly focusing on manufacturing conditions, e.g. of meat, soy, palm oil and cocoa. The United States Congress is also fine tuning a proposal for a supply chain law against deforestation. But what do we achieve through supply chain laws?

One thing is certain: The more countries that impose requirements on companies, the fewer opportunities there are for so-called leakage effects.

This means that any countries and producers that either cannot or do not want to comply with supply chain legislation will seek markets with less stringent requirements. One argument against the German Supply Chain Act is that it only affects companies based in Germany. This puts German companies at a disadvantage in international competition and does not address the leakage effects sufficiently. At the EU level, this is to be handled differently and will affect all companies wanting to sell within the EU.

To prevent a shift in global trade, so-called due diligence requirements must be implementable and effective. However, opinions are already divided on both issues: Is it reasonable to demand that companies monitor and address not only the environmental and social malpractices of their own subsidiaries, but also of their suppliers and the suppliers of their suppliers? There is a risk that European companies will withdraw from certain countries or regions because they find it too troublesome to address any violations there. This would have a negative impact on local producers. And what moral authority or political right does Europe have to call for “deforestation-free” agricultural production in poorer countries, considering its own unparalleled history of industrial deforestation?

On the other hand, there is scientific proof that productivity in cocoa, coffee and soy decreases in proportion with the disappearance of forests, as this results in local climate change. The preservation of forests would therefore also be in the long-term economic interests of farmers and producers in Brazil and Côte d’Ivoire. Global supply chains are long and often complicated. The journey of cotton from an African plantation to a T-shirt involves numerous stages of processing, transport and trading. It is therefore by no means trivial to hold a textile seller responsible for the production process of the cotton or oil from which the fibres were produced. On the other hand, companies are already highly successful in making demands on their suppliers in terms of quality. They often do so simply to preserve their good reputation. In the agricultural sector, the problem that still needs to be solved is the transparency of the “first mile”, for example, the journey from the cocoa farmer to the cooperative. In the case of subcontracted supplies, it is sometimes impossible to verify whether the cocoa comes only from cooperative members or whether it has been purchased from unregistered farmers who may have conducted forest clearances recently. However, here, too, companies have found (sometimes digital) solutions to make this clear.

Another transparency issue in supply chain management is economic complexity: There is a profound lack of knowledge about who earns how much money where and at which stage.

A 2020 study by the Innovation Forum states: “We understand too little about the aspects of income, health and safety at workplaces along the value chains between a farm and a seaport.”Apparently, even international corporations often do not have enough relevant internal data on the production conditions of agricultural raw materials. For example, farmers who live on cocoa or coffee cultivation are often encouraged to grow several crops – either for agricultural reasons or to diversify their income. However, this greater commitment to sustainability is often not rewarded in the marketing of cocoa or coffee raw materials. The same applies to agriculture in agroforestry systems, which are recommended by many agronomists.

The situation of the producers is often desperate: In Kenya, for example, the earnings of nearly 70 percent of all tea farmers are below the poverty line as defined by the World Bank. Only 10 percent among them managed to achieve an adequate living income in 2014. Although not all cocoa and coffee farmers in Africa have it as desperately bleak, poverty does tend to prevail. A look at the figures reveals the magnitude of the challenge of effectively improving the situation of these people: According to a study by Wageningen University in the Netherlands in 2019, over half of all tea and cocoa farmers would have to more than double their earnings in order to earn a living income. This goal seems unattainable but would be possible if companies and consumers at the end of the supply chain paid just a few cents more per product unit. However, this money would have to reach the individual farmer in full, which is why traceability and transparency in the supply chain are so important. In places where incomes for plantation work are lowest, appropriately worded supply chain laws might be the best way to generate impact without causing displacement – for instance, by requiring only modest increases in incomes. This is the case in cocoa farming, for example. However, fair incomes and wages are also a human right.

Article 23 of the UN Convention on Human Rights states: "Everyone has the right to equal pay for equal work. Everyone has the right to just remuneration ensuring an existence worthy of human dignity."

In the future, there will be greater clarity about the points along the supply chain where value creation is high and where it is low. To gain more knowledge about eco-social issues and to boost value creation, a good deal of hope is currently being placed in digital technology. It now seems possible to conduct direct marketing over long distances, while transparency and traceability can be enhanced through technical solutions. According to an OECD study, “a range of technologies are contributing to the digital transformation of operations in the food sector and trade: electronic data exchange, platforms and sensors, the internet of things, cloud computing, big data, artificial intelligence and block chain.”All these are set to change the agricultural sector in the future, leading to product differentiation and creating new markets.

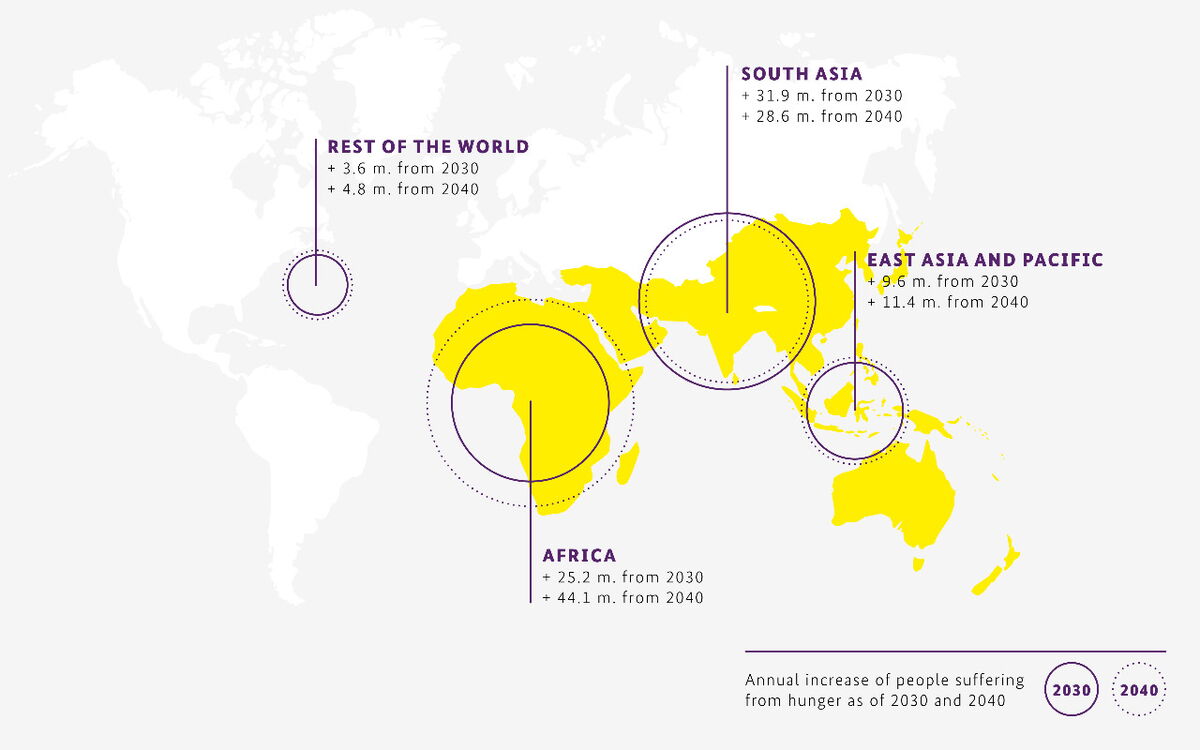

In addition to changing the rules of the trade game, regulations are needed on the ground, so that smallholders can be lifted out of poverty. In Africa and Southern Asia their land is often too small, productivity is too low, and farmers “who cannot earn more than a living income need alternative employment opportunities, so that they can leave agriculture,” according to the study from Wageningen. The responsibility therefore also lies with the countries of the Global South themselves. As sovereign states, Tunisia, Indonesia, Bangladesh or Kenya are no different from Germany when it comes to respecting human rights within their own territories. Economic development, access to government services such as good education, and the management of property rights are also the responsibility of state governments.

Due diligence mechanisms regulated by supply chain legislation are still in their infancy, which is why there is still very little information about their direct and indirect effects. On the other hand, the situation for labels is different, some of which have been in place for decades. According to Michael Brüntrup of the German Development Institute, voluntary standards are preferable to strict legal requirements that have high barriers in terms of wages, prices or green farming requirements. As regards voluntary standards such as labels (e.g. organic and fairtrade), a study has shown the positive impact on both income and the social situations of smallholders (Meemken 2020). The meta-study mentions substantial increases, averaging 52 percent in the yield of participating farms, 19.6 percent in the prices achieved and 16 percent in household incomes. Contrastingly, Brüntrup says that many state regulations do not lead to price mark-ups and would force smaller and weaker farms out of the market.

Other studies show that labels are not sufficient in themselves. The German Leibnitz Institute (ZALF) has been studying international literature, focusing on the example of cocoa farming. The results were less clear-cut. The per-hectare income on certified farms in Côte d’Ivoire increased by a third, as did harvests and productivity (Schulte 2020). Furthermore, certification has led to improvements in the working conditions of farmworkers and to increased local awareness of the problem of child labour. However, it was far from possible to solve the problem for the entire sector. Also, the proportion of child labour in cocoa-growing areas in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire rose from around 31 percent to 45 percent between 2008 and 2018. One reason was strong population growth coupled with a simultaneous lack of schools and jobs. Such systemic problems cannot therefore be solved through certification standards alone.

The question remains whether regulations imposed by importing countries can improve the situation or whether regulations would need to come from the producing countries themselves.

Numerous small-scale successes are offset by a large-scale downward trend: Although water quality and soil fertility have improved on certified farms, the West African rainforest has continued to dwindle in favour of plantations. Another reason why certification is by no means a miracle cure is that it does not impact the entire area, but merely creates “green islands” of certified plantations. Due diligence regulations for deforestation-free supply chains should therefore oblige all companies to refrain from expanding their acreages by clearing or burning forests. However, the additional expenditure incurred by producers complying with certification criteria is still not fully rewarded by the market, as farmers are often unable to sell all their produce at appropriately higher prices. As a result, producers are forced to sell their more expensively produced items on the conventional market.

The third sphere of action – in addition to voluntary certification and forthcoming mandatory due diligence laws – is the vast array of international trade regulations already in place. One example is conditional reductions in customs tariffs in cases where certain international environmental and social standards are signed by partner countries (such as the European GSP+). Moreover, references to sustainability can also be found in bilateral and regional trade agreements such as Mercosur, but these would often need to be made more mandatory. One relatively new legal tool for the EU is that the term “dumping” can also be interpreted as non-compliance with socio-environmental standards and can result in customs tariff protection. Furthermore, the regulations of the WTO – designed to strengthen free trade – do actually allow for exceptions. This makes it possible, for example, to pay subsidies to farmers for compliance with environmental targets, for social justice or for anti-poverty measures. However, for financial reasons, developing countries rarely use such subsidies.

For all the EU’s strengthening of sustainability in international trade, it should be noted that many developing countries are united by concerns about green protectionism. They accuse the EU of wanting to protect its domestic market through such trade regulations. However, requiring companies to comply with due diligence regulations is not meant to impose restrictions on trade, but to ensure that companies address malpractices within their supply chains – although the envisaged purpose and the actual effect may differ. One particular observation about sustainability in supply chains is frequently repeated in the discussion: the idea that we need a “smart mix”. This means an interdependent mix of rules for companies, government regulations, voluntary commitments and support for partner countries and farmers. The idea is to have a balanced international trading system that strengthens not only free trade, but also sustainability. What we need most, however, are actors who accept responsibility for ensuring human rights and environmental protection at all stages of production. After all, the paper has remained patient for over 60 years, but humans and nature are still suffering daily for our consumption.

We would like to express our grateful thanks for all the expert advice we have received and the many discussions we have had with Michael Brüntrup (German Development Institute, DIE), Bettina Rudloff (German Institute for International and Security Affairs, SWP) and Maike Moellers (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GIZ GmbH).

Bibliography

- Greenville, Jared et al. (2017), How policies shape global food and agriculture value chains, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, 100, Paris.

- Jouanjean, Marie-Agnés (2019), Digital Opportunities for Trade in the Agriculture and Food Sectors, OECD Food, Agricultureand Fisheries Papers, 122, Paris.

- Meemken, Eva-Marie (2020), Do smallholder farmers benefit from sustainability standards? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Food Security, 26.

- Bettina Rudloff, Christine Wieck (2020), Sustainable Supply Chains in the Agricultural Sector: Adding Value Instead of Just Exporting Raw Materials. Corporate Due Diligence within a Coherent, Overarching and Partnership-based EU Strategy, SWP Comment 2020/C 43,

- Schulte, Ingrid et al. (2020), Supporting Smallholder Farmers for a Sustainable Cocoa Sector: Exploring the Motivations and Role of Farmers in the Effective Implementation of Supply Chain Sustainability in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Supply Chain Sustainability Research Fund.

- Stanbury, Peter (2020), Building resilient smallholder supply chains, How to enable transformation for farmers, institutions and supply chains, Innovation Forum.

- Waarts, Yuca et. Al. (2019), A living income for smallholder commodity farmers and protected forests and biodiversity: how can the private and public sectors contribute?, Wageningen Economic Research White paper on sustainable commodity production.